Saturday, April 06, 2019

Hand shadows

God and gender

Friday, April 05, 2019

Dogs and babies

Compare this to women who "rescue" dogs from animal shelters, then have "dog mom" bumper stickers.

War on reality

Part of the reason for this is that once you deny God, then reality ceases to be normative. In naturalism, reality is arbitrary. A blind surd. So why not rebel against reality?

Naturalism and unitarianism

Thursday, April 04, 2019

The origin of the Easter Bunny

– Wesley Huff

Is Heb 1 about the new creation?

The point of the catena [in Heb 1] is to demonstrate Jesus's superiority to the angels - or. better, difference in kind from the angels. It does not have to all relate to the exalted Jesus, but works with the standard Jewish correlation of "God is the only Creator of all things" and "God is the only sovereign Lord of all things.""The beginning" is virtually a technical term for the primordial time at the beginning of everything (Gen 1:1; Prov 8:22-23; John 1:1)."You founded [past tense] the earth and the heavens ..." would be utterly unparalleled as a way of referring to the new creation. For the NT, the new creation of heaven and earth is still very much future (Rev 21; Acts 3:21). Only in the case of individual Christians can new creation be said to have already happened (2 Cor 5:17).The new creation, when it comes, will not perish (Heb 12:27).Tuggy's exegesis is ridiculously forced and quite obviously special pleading.

The Song of Songs

The couple in Song of Songs was not married. Or engaged. The most literal reading of the Bible is that they were sneaking around having wild and enthusiastic premarital sex.

— Lura Groen (@lura_groen) April 3, 2019

I’m sorry people have been telling you lies about this.

i) Apparently, Lura is ordained in the ELCA.

ii) To the contrary, the couple seems to be bride and groom. And as one commentator observes:

The centerpiece of the book is a wedding scene that concludes with the consummation of their relationship. Iain Duguid, The Song of Songs: An Introduction and Commentary (IVP 2015), 41.

iii) It's artificial to isolate the sexual mores in the Song of Songs from Proverbs or the Mosaic Law.

iv) The "most literal reading"? This isn't a prosaic narrative, but a highly stylized set of love poems with a loose narrative thread.

v) Unfortunately for Lura, it's overwhelmingly heteronormative.

vi) I think the book is a fictional depiction of the sexual fantasies of a man and woman engaged to be married. Erotic poetry to celebrate the sexual passion and anticipation of the bride and groom. That accounts for the blurry, fluid, dream-like plot.

"No crying he makes"

Josephus, Synoptics, and the argument from silence

Outside NT, Josephus is the main historian for Palestine during Jesus' life.— Peter J. Williams (@DrPJWilliams) March 28, 2019

His Antiquities Bk 18 covers 32 yrs ca. AD 6-38.

At ca. 15,764 words it's shorter than Matt (18,347)/Luke (19,463)

He has <500 words/yr.

It's absurd to think he should mention everything significant.

Wednesday, April 03, 2019

Memoirs and memories

Do The Resurrection Accounts Fabricate Evidence?

Notice the irony in the fact that many of these same critics will object to the brevity of the accounts in Matthew and Mark. That sort of brevity doesn't sit well with the idea that the authors or their sources were trying to pad their case with fake evidence. Even the passages in Luke, John, Acts, and elsewhere are relatively short. The resurrection was so central to all of the gospels that they all conclude just after it, and it's treated as a foundational event in other ways, yet the resurrection accounts only take up a small percentage of the documents.

More significantly, think of the large amount of material they could have included, but didn't. There's no description of the resurrection itself. The empty tomb is discovered by some of Jesus' female followers rather than other witnesses who would have been considered more appropriate and more credible. There's no narration of the appearance to James, even though every gospel portrays him as an unbeliever, which makes his conversion after seeing the risen Jesus so important. (For documentation that all of the gospels portray James as an unbeliever, see Eric Svendsen's Who Is My Mother? [Amityville, New York: Calvary Press, 2001].) None of the gospels include the appearance to Paul. If the appearance to more than five hundred mentioned in 1 Corinthians 15:6 is narrated by anybody, it's done without mentioning that so many individuals were involved. Matthew's reference to the physicality of Jesus' body in 28:9 is incidental, and Matthew, Luke, and John's accounts of physicality are accompanied by accounts of people doubting or not recognizing Jesus (Matthew 28:17, Luke 24:16, 24:37-38, John 20:15, 21:4). Ancient Jewish literature frequently portrayed resurrected individuals and other exalted figures in glorious terms (Daniel 12:3, 2 Maccabees 15:13, Matthew 13:43), yet the gospels don't describe the resurrected Jesus that way.

Luke's gospel provides a good illustration of the sort of restraint I'm referring to. Given the earliness of the resurrection creed cited in 1 Corinthians 15 and Luke's close relationship with Paul, Luke probably knew about the appearances to James, Paul, and the more than five hundred. He portrays James as a believer and an apostle in Acts, and he narrates the appearance to Paul there. So, he seems to know about the resurrection appearances to James, Paul, and the more than five hundred, even though he only narrates one of them and waits until several chapters into Acts to do it. Jesus' body and general appearance are described in glorious terms in Luke's accounts of the Mount of Transfiguration and the resurrection appearance to Paul in Acts. Even the angels at Jesus' tomb are described in glorious terms (Luke 24:4-5). But the resurrected Jesus isn't described that way at the close of Luke's gospel or the opening of Acts. I could mention other examples, but these are more than enough to illustrate my point.

The impression given by the gospels and other early sources is that they had a large amount of resurrection evidence to draw from, but were satisfied with citing some representative examples. John 21:25 just about says that.

The rest of church history illustrates what I'm referring to. Even after Matthew's gospel became widely accepted, for example, the guards at the tomb weren't often brought up when Christians were arguing for their religion or the resurrection in particular. The guards offer a significant line of evidence for the resurrection, but they're just one significant line among many others. When I discuss the evidence for the resurrection, sometimes I cite the guard account, and sometimes I don't. Matthew probably included it because of its relevance to Judaism and the leaders of Judaism, to whom he was responding to such a large extent in his gospel. The other gospel authors had no need to include that material and thought that what they did include was adequate.

The earliest Christians don't seem to have been so desperate for resurrection evidence that they were making up stories about guards at the tomb, people touching Jesus' resurrection body, etc. Rather, many modern critics want to dismiss every such detail in the accounts, even if the details are offered so sparingly and surrounded with so much restraint. The early Christians were biased, but their critics have biases of their own.

Tuesday, April 02, 2019

Broflake

The lynching of Jesse Washington

It is sometimes claimed that Christians who reject hell as eternal conscious torment do so out of "sentimentalism". As if moral horror at the prospect of human beings suffering torture forever is being "too sentimental"? What a grotesque assertion!— Tentative Apologist (@RandalRauser) April 2, 2019

Monday, April 01, 2019

Me, myself, and I

Chronological time

"We don't know what Jesus looked like"

Atonement by crucifixion

Sunday, March 31, 2019

Progressive Christianity

Liberal Christian theology is like someone who started out with a luxury car but over time had to strip it down to a set of wheels that has to be pushed.— Tim Sledge (@Goodbye_Jesus) March 31, 2019

You've got to admire the determination to not give up on the car.#exchristian

Is God incoherent?

First consider the attribute of omnipotence. You’ve probably heard the paradox of the stone before: Can God create a stone that cannot be lifted? If God can create such a stone, then He is not all powerful, since He Himself cannot lift it. On the other hand, if He cannot create a stone that cannot be lifted, then He is not all powerful, since He cannot create the unliftable stone. Either way, God is not all powerful.

Can God create a world in which evil does not exist? This does appear to be logically possible. Presumably God could have created such a world without contradiction. It evidently would be a world very different from the one we currently inhabit, but a possible world all the same. Indeed, if God is morally perfect, it is difficult to see why he wouldn’t have created such a world. So why didn’t He?The standard defense is that evil is necessary for free will... However, this does not explain so-called physical evil (suffering) caused by nonhuman causes (famines, earthquakes, etc.). Nor does it explain, as Charles Darwin noticed, why there should be so much pain and suffering among the animal kingdom.

What about God’s infinite knowledge — His omniscience? …If God knows all there is to know, then He knows at least as much as we know. But if He knows what we know, then this would appear to detract from His perfection. Why?There are some things that we know that, if they were also known to God, would automatically make Him a sinner, which of course is in contradiction with the concept of God. As the late American philosopher Michael Martin has already pointed out, if God knows all that is knowable, then God must know things that we do, like lust and envy. But one cannot know lust and envy unless one has experienced them. But to have had feelings of lust and envy is to have sinned, in which case God cannot be morally perfect... But if God doesn’t know what we know, God is not all knowing, and the concept of God is contradictory. God cannot be both omniscient and morally perfect. Hence, God could not exist.

Escaping from the Hornets’ Nest

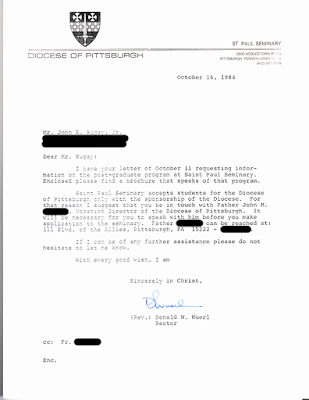

The letter is a response to me by Donald Wuerl, who now is the disgraced Cardinal Archbishop of Washington DC, having forgotten that he knew about Cardinal McCarrick’s homosexual abuse of minors and Roman Catholic seminarians, but who then (1984) was the rector of St. Paul’s Seminary in Pittsburgh.

I had apparently written to him requesting information about admission to the Seminary, and in this letter, he referred me to the “Vocations Director” for the Diocese of Pittsburgh. By the end of that year, I had applied for and was accepted to this seminary program, and I remember having attended a small lunch at the Seminary, for incoming students, that was hosted by then Father Wuerl. That’s where I met him.

Most people know me as someone who knows Roman Catholicism in a very thorough way. My Protestant friends look to me for advice when they interact with Roman Catholicism in one way or another. Some Roman Catholics know me as an apostate, and some (Dave Armstrong Google Alert) consider me to be a bitter anti-Catholic.

But this letter reveals my bona-fide credentials as a genuine Roman Catholic, back in the day.

To make a long story short ...