Saturday, January 27, 2018

Morally corrosive

Is the canon a fallible list of infallible books?

To put it briefly, Rome believes that the New Testament is an infallible collection of infallible books...The historic Protestant position shared by Lutherans, Methodists, Episcopalians, Presbyterians, and so on, has been that the canon of Scripture is a fallible collection of infallible books…Also there was the issue of authority, and the principle that emerged among Protestants was that of sola scriptura, which means that Scripture alone has the authority to bind our conscience. Scripture alone is infallible because God is infallible. The church receives the Scripture as God’s Word, and the church is not infallible. That is the view of all Protestant churches.

https://www.ligonier.org/learn/qas/we-talk-bible-being-inspired-word-god-would-men-wh/

Non serviam

Friday, January 26, 2018

Invisible friendship

Richard DawkinsVerified account@RichardDawkinsTheists: you get comfort in the imaginary embrace of an imaginary friend? Try real warm embrace of a real warm friend. That's real comfort.

The scientific community

I noticed an atheist make the following comments to which I'd like to respond:

The entire scientific community accepts Darwinian evolution (not "intelligent design"), climate change, the complex mental life of animals, and the big bang theory.

1. What's his source that "the entire scientific community accepts Darwinian evolution"? For example, James Shapiro (University of Chicago) argues for natural genetic engineering while Stuart Kauffman (University of Pennsylvania) argues for self-organization and far-from-equilibrium dynamics in evolutionary theory. These concepts would be in tension with natural selection, the role of random mutations in developing novel body plans and structures, among others.

2. If it's true "the entire scientific community accepts...the big bang theory", and presumably this atheist accepts the big bang theory on their authority, then it's possible to argue the big bang theory (as well as other aspects in contemporary cosmological theories) supports creatio ex nihilo which in turn would support an argument for God's existence.

So you agree there is no place for God in explaining complex life? Good, that puts you in good company with the 98% NAS members.

1. Methodological naturalism quite arguably limits rather than expands scientific investigation and discovery. It defines what's allowable and disallowable in advance of actually performing science. That potentially excludes the exploration of legitimate phenomena.

2. The National Academy of Sciences consists of maybe 2500-3000 members. That's only a percentage of all the scientists in the world let alone throughout history.

3. The vast majority of the members are American. Is it any surprise a secular country has a lot of secular scientists in their scientific academies? To say nothing of a secular country that has it in for scientists and other scholars who are theists (e.g. intelligent design theorists). For instance, watch Ben Stein's Expelled.

4. Membership to the National Academy of Sciences may be prestigious, but what does prestige have to do with truth?

5. In my view, the National Academy of Sciences amounts to an inflated social club. Like any social club, there are politics involved in who is accepted or rejected as a member. I'd hope the politics don't ever become biased or prejudiced, but I doubt it.

On a related note, Richard Feynman once had some choice words about honors and suchlike:

When I was in high school, one of the first honors I got was to be a member of the Arista, which is a group of kids who got good grades. Everybody wanted to be a member of the Arista. When I got into the Arista, I discovered that what they did in their meetings was to sit around and discuss who else was worthy to join this wonderful group that we are. Okay, so we sat around trying to decide who it was who would get to be allowed into this Arista. This kind of thing bothers me, psychologically, for one or another reason. I don't understand myself. Honors, from that day to this, always bothered me. I had trouble when I became a member of the National Academy of Sciences and I had ultimately to resign because there was another organization most of whose time was spent in choosing who was illustrious enough to be allowed to join us in our organization, including such questions as "we physicists have to stick together because there's a very good chemist that they're trying to get in and we haven't got enough room". What's a matter with chemists? The whole thing was rotten, because the purpose was mostly to decide who could have this honor. Okay, I don't like honors.

6. There are good scientists doing good scientific work who aren't members of the National Academy of the Sciences. Not to mention there have been good scientists doing good scientific work who have resigned from the National Academy of Sciences.

7. If this is more about scientists being atheists, there are many scientists today as well as in the past who aren't atheists but who do believe in God. In the present, some examples are Francis Collins, James Tour, Henry Schaefer, Don Page, and Juan Maldacena. In addition, the Pew Research Center (2009) finds 51% of scientists believe in God or a similar higher power.

8. At the risk of stating the obvious, the National Academy of Sciences consists primarily of scientists. Scientists qua scientists have no special knowledge or expertise when it comes to arguing for or against God's existence. (Nor arguing for or against methodological naturalism.) It'd be better to turn to philosophers of religion if he wants the best arguments for or against God's existence.

Let me introduce you to my invisible friend

Richard DawkinsVerified account@RichardDawkinsTheists: you get comfort in the imaginary embrace of an imaginary friend? Try real warm embrace of a real warm friend. That's real comfort.

Thursday, January 25, 2018

Psychological time-travelers

Is an Incarnation alien to Judaism?

On Jordan's bank

How did Pharisees commit an unforgivable sin?

Wednesday, January 24, 2018

Should women teach in seminaries?

https://www.desiringgod.org/interviews/is-there-a-place-for-female-professors-at-seminary

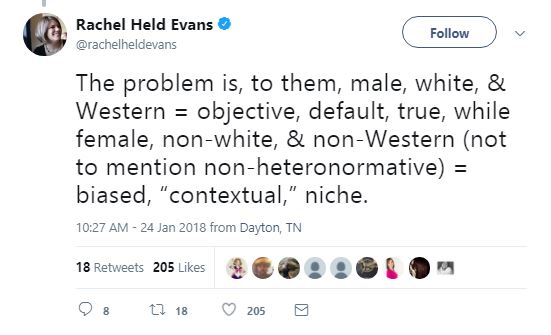

Funny to see the shocked reaction, as if he doesn't have a mile long paper trail on these issues. Here was the funniest reaction I've seen:

As if the Patriarchy is a white Western invention. As if non-white, traditional Third-World cultures are egalitarian and non-heteronormative.

On this issue I agree with Piper in some respects, but not in others. Before getting to the main point, I'll make some ancillary observations:

i) I don't think it's coincidental that Piper is an older generation Southerner. I expect his complementarianism is largely a continuation of a traditional Southern chivalric code. I don't say that as a criticism.

ii) He somewhat overstates the purpose of seminaries. Although they basically exist to train pastors, they offer MAR degrees as well as MDiv degrees.

iii) Although he bases his position on a complementarian reading of 1 Tim 2:12, he doesn't seem to object to women wielding authority over men in principle or women teaching men in principle. He doesn't seem to object to female professors at a Christian college. Rather, his argument is geared to the nature of pastoral formation.

iv) I agree with him on complementarianism.

v) I agree with him that it's ad hoc to say women can teach men to teach parishioners, but women can't teach parishioners directly.

vi) He oversimplifies pastoral ministry. A pastor of a small church does everything. By contrast, megachurches have compartmentalized ministries. Due to the size of the congregation, the ratio of pastor to parishioner, and the financial resources of a megachurch, what one man must do singlehandedly when pastoring a small church gets delegated to several different ministers at a megachurch.

That complicates his complementarianism. Take visitation ministry or a woman's Bible study.

vii) Does Piper think it's permissible for a pastor to read a commentary by Karen Jobes, but not to attend a class by Karen Jobes? If so, what's the essential difference?

viii) A good pastor doesn't necessarily have the same skill set as a good seminary prof, or vice versa. Seminary professors can outstanding scholars or thinkers, but abysmal communicators. Likewise, great scholars and thinkers may be sorely deficient in social skills.

ix) Now I'd like to get to the main point. I disagree with Piper's position on this particular issue. The rationale Piper gives for his position is unwittingly at odds with complementarian anthropology. Sophisticated complementarians aren't voluntarists. They don't think Biblical gender roles are arbitrary social constructs. Rather, they think these mirror stereotypical physical and psychological differences between men and women.

Yet Piper unintentionally acts as if these roles are interchangeable. He thinks that if male seminarians view male seminary profs. as pastoral role models, and if you put a woman in the same slot, then male seminarians will view women as pastoral role models.

Which ironically assumes that men relate to women the same way they relate to men when women occupy the same social role or institutional position. But I find that highly dubious and contrary to complementarian anthropology.

In my observation, men measure themselves by other men while women measure themselves by other women. Men don't measure themselves by women and women don't measure themselves by men. The psychological dynamic between men and women is different even when the social roles or institutional positions are artificially the same.

That's one reason we defend heterosexual marriage. Mothers can't take the place of fathers while fathers can't take the place of mothers. Kids need both. One person can't successfully play both roles.

The father/son dynamic, mother/son dynamic, father/daughter dynamic, mother/daughter dynamic, brother/brother dynamic, brother/sister dynamic, and sister/sister dynamic are all different.

Suppose the military put a woman in charge of a Navy SEAL team. Would the male members of that team relate to her the same way they relate to a male comrade just because she was given the same position? Are you kidding me?

Another example is the difference between male and female hymnodists. Male hymnodists have a different sensibility than female hymnodists.

I think it's wholly unrealistic to suppose that if a normal man has a female seminary professor, he will view her the same way he'd view a male seminary professor, as though male-on-male psychology is transferable to male-on-female psychology. This is not to deny that men can look up to women, and women can look up to men–but it doesn't mean they're consciously or subconsciously thinking that a member of the opposite sex embodies what they aspire to be like. That's just not how human nature is wired. Women are not an example of how to be a man. Men are not an example of how to be a woman.

There are, of course, some generic virtues they can share in common. Some Christian women exhibit perseverance in adversity or even moral heroism. We can admire that in members of either sex. But by the same token, that's not a lay/clerical distinction.

Motives of credibility

The motives of credibility establish with moral certainty the divine origin and divine authority of the Catholic Church [314]Here again you’re conflating the period of inquiry and the life of faith, as if what one in the period of inquiry would do entails epistemic equivalence between Protestants on the one hand, and on the other, Catholics living the life of Catholic faith. But a person in the period of inquiry is not in the epistemically equivalent state of the Catholic living the life of faith. Moreover, what would hypothetically serve as a motive of discredibility in the period of inquiry would not be even possible for that entity in which, through the motives of credibility, one may come to divine faith... The Catholic in the life of faith knows that the Church through God’s divine protection cannot teach false doctrine, and is therefore not subjecting the Church’s doctrine to the judgment of his own interpretation of Scripture, but instead allowing the Church to guide and form his interpretation of Scripture.Again, this conflates the period of inquiry into the motives of credibility, with the life of faith. The person in the stage of inquiry into the motives of credibility is, like the Protestant, not in an epistemic position of acknowledging and submitting to a divinely authorized magisterium. But that does not mean or entail that the Catholic living the life of faith, and thus having come to know and believe in the divine authority of the Church Christ founded, is in the same epistemic condition as the inquirer, or as the Protestant [#324]

God makes known His voice by way of marks that are unmistakable, i.e. something that only God can do (i.e. miracles). These are what are called the motives of credibility, by which we recognize God’s word as God’s word. (2′)Motives of credibility allow us to make the transition from human faith to divine faith. (3′)The motives of credibility allow the act of faith to be reasonable, and make the act of disbelief unreasonable; without them the act of faith would be unreasonable, and would lay us open to superstition. (3′)Four categories of signs serving as motives of credibility:(1) miracles, (5′)(2) prophecies (6′)(3) the Church (7′)(4) the wisdom and beauty of revelation itself, and Christ Himself (7′)The Catechism on the motives of credibility (8′)Thus the miracles of Christ and the saints, prophecies, the Church’s growth and holiness, and her fruitfulness and stability “are the most certain signs of divine Revelation, adapted to the intelligence of all”; they are “motives of credibility” (motiva credibilitatis), which show that the assent of faith is “by no means a blind impulse of the mind.” (CCC 156)

Tuesday, January 23, 2018

Self-identify as fit for communion

https://www.firstthings.com/web-exclusives/2018/01/mr-fit-goes-to-communion

I'll do for you if you do for me

Facts don't care about your feelings

http://nymag.com/daily/intelligencer/2018/01/sullivan-metoo-must-choose-between-reality-and-ideology.html

Jesus Is All the World to Me

https://epistleofdude.wordpress.com/2018/01/22/mabel-and-the-emotional-problem-of-suffering/

Blinker hood

Protestantism itself has no visible catholic Church. It has only denominations, congregations, believers and their children. Within Protestantism there is not some one additional entity to which the term “visible catholic Church” refers, consisting of these denominations, congregations, believers and their children...What allowed the authors of the Westminster Confession to believe sincerely that there was a “visible catholic Church” other than the Catholic Church headed by the Pope, was a philosophical error. This was the error of assuming that unity of type is sufficient for unity of composition. In actuality, things of the same type do not by that very fact compose a unified whole. For example, all the crosses that presently exist all have something in common; they are each the same type of thing, i.e. a cross. But they do not form a unified whole composed of each individual cross around the world. This crucifix, for example, in the St. Louis Cathedral Basilica, is not a part of a unified whole consisting of all the crucifixes in the world. All crucifixes are things of the same specific type, but that does not in itself make them parts that compose a unified whole spread out around the world...One way to determine whether something is an actual whole or merely a plurality of things......when Matthew records Jesus saying to Peter in Matthew 16:18, “upon this rock I will build My Church”, and then saying, in Matthew 18:17, “tell it to the Church”, and “listen to the Church”, the most natural way of understanding these passages is that the term ‘ekklesia’ (‘Church’) is being used in the same way in all three places. And it is clear in the Matthew 18 passages that ‘ekklesia’ there refers to the visible Church, not a merely spiritual entity.

Helicopter parents

Monday, January 22, 2018

Fireproof

20 And he ordered some of the mighty men of his army to bind Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego, and to cast them into the burning fiery furnace. 21 Then these men were bound in their cloaks, their tunics,[e] their hats, and their other garments, and they were thrown into the burning fiery furnace. 22 Because the king's order was urgent and the furnace overheated, the flame of the fire killed those men who took up Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego. 23 And these three men, Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego, fell bound into the burning fiery furnace.24 Then King Nebuchadnezzar was astonished and rose up in haste. He declared to his counselors, “Did we not cast three men bound into the fire?” They answered and said to the king, “True, O king.” 25 He answered and said, “But I see four men unbound, walking in the midst of the fire, and they are not hurt; and the appearance of the fourth is like a son of the gods.”26 Then Nebuchadnezzar came near to the door of the burning fiery furnace; he declared, “Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego, servants of the Most High God, come out, and come here!” Then Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego came out from the fire. 27 And the satraps, the prefects, the governors, and the king's counselors gathered together and saw that the fire had not had any power over the bodies of those men. The hair of their heads was not singed, their cloaks were not harmed, and no smell of fire had come upon them (Dan 3:20-27).

Polycarp 15:2The fire, making the appearance of a vault, like the sail of a vessel filled by the wind, made a wall round about the body of the martyr; and it was there in the midst, not like flesh burning, but like [a loaf in the oven or like] gold and silver refined in a furnace. For we perceived such a fragrant smell, as if it were the wafted odor of frankincense or some other precious spice.Polycarp 16:1So at length the lawless men, seeing that his body could not be consumed by the fire, ordered an executioner to go up to him and stab him with a dagger. And when he had done this, there came forth [a dove and] a quantity of blood, so that it extinguished the fire; and all the multitude marvelled that there should be so great a difference between the unbelievers and the elect.