|

| Medieval conception of Purgatory |

In his work “The Reformation: A History”, Diarmiad MacCulloch gives a brief overview of the Roman Church prior to the Reformation. He introduces that overview with this passage:

Nicholas Ridley, one of the talented scholarly clergy who rebelled in England against the old [Roman] Church, wrote about this to one of his fellow rebels John Bradford in 1554, while they both lay in prisons waiting for the old Church to burn them for heresy. As Bishop Ridley reflected on the strength of their deadly enemy, which now he saw as the power of the devil himself, he said that Satan’s old world of false religion stood on two ‘most massy posts and mighty pillars … these two, sir, are they in my judgement: the one his false doctrine and idolatrical use of the Lord’s supper; and the other, the wicked and abominable usurpation of the primacy of the see of Rome … the whole system of the medieval western Church was built on the Mass and on the central role of the Pope. Without the Mass, indeed, the Pope in Rome and the clergy of the Western Church would have had no power for the Protestant reformers to challenge, for the Mass was the centerpiece around which all the complex devotional life of the Church revolved (Diarmiad MacCulloch, “The Reformation: A History” (New York, NY: Penguin Books, ©2004, pg 10).

These are the things that the Reformation was all about: the “Mass” and the Papacy. These were the two real bulwarks of Roman strength. But in what way did they exercise power in the 16th century? In what ways did they hold captive the entire continent of Europe?

I’ve written extensively about the papacy. This Reformation Season, I’d like to start by talking about the Mass, and how that affected the lives of people during the middle ages; I’ll follow MacCulloch’s treatment with some amplification where necessary; for “the Mass” was not a simple topic. The whole of the Roman religion revolved around it (and still does).

Here is MacCulloch’s overview

The Mass and Purgatory

The word ‘Mass’ is a western nickname for the Christian Church’s central act, the service of Eucharist. It comes from a curiously inexplicable dismissal at the end of the Latin Eucharistic liturgy – ‘ite missa est (‘go, it is sent’). To appreciate the importance of the Mass an explanation of what Christians believe about the Christian Eucharist is needed. They see it as a representation, or perhaps dramatic re-creation of the last supper from which Jesus Christ ate with his disciples before his death….

The Eucharist became a drama linking Christ to his followers, pulling them back to his mysterious union with the physical world and his conquest of the decay and dissolution of the physical in death. It was such a sacred and powerful thing that by the twelfth century in the Western Church, the laity dared approach the Lord’s table only very infrequently, perhaps once a year at Easter, otherwise leaving their priest to take the bread and wine while they watched in reverence. Even when laypeople did come up to the altar, they received only the bread and not the wine, a custom which has never received any better explanation than that there was a worry that the Lord’s blood might stick in the moustaches and beards of the male faithful. [For more on this see Luther’s work “On the Babylonian Captivity of the Church”.] But the particular power of the Mass in the medieval West comes from its association with another idea peculiar to the Western Church: this most powerful form of public liturgical prayer may be concentrated and directed to steer individuals through the perils of death to God’s bliss in the afterlife (pgs 10-11).

This “concentration” came in the form of “help getting out of purgatory”. More specifically, to use the words of Trent, “in this divine sacrifice” (Council of Trent, Session XXII, see Denzinger, 940) “which is celebrated in the Mass, that same Christ is contained and immolated in an unbloody manner, who on the altar of the Cross “once offered Himself” in a bloody manner [Heb. 9:27], the holy Synod teaches that this is truly propitiatory [can. 3], and has this effect, that if contrite and penitent we approach God with a sincere heart and right faith, with fear and reverence, “we obtain mercy and find grace in seasonable aid” [Heb. 4:16]. For, appeased by this oblation, the Lord, granting the grace and gift of penitence, pardons crimes and even great sins. For, it is one and the same Victim, the same one now offering by the ministry of the priests as He who then offered Himself on the Cross, the manner of offering alone being different. The fruits of that oblation (bloody, that is) are received most abundantly through this unbloody one; so far is the latter from being derogatory in any way to Him [can. 4]. Therefore, it is offered rightly according to the tradition of the apostles [can 3], not only for the sins of the faithful living, for their punishments and other necessities, but also for the dead in Christ not yet fully purged (emphasis added).

Rome holds that it is Christ on the Cross re-presented in an “unbloody” way in the Mass. Though it is “one and the same sacrifice of Christ” that is offered each time. (Anyone who wants to read current Roman Catholic teaching on “the Eucharist” and “the Sacrifice of the Mass” can find it beginning here)

Now, many have pointed out the unbiblical nature of the Roman “sacrifice” – that somehow, you can be the recipient of this largesse from Christ, (and in fact, you can be such a recipient, day after day, week after week), and still suffer from “an inability to be fully cleansed” (James R. White, The Roman Catholic Controversy”, Minneapolis, MN: Bethany House Publishers, ©1996, pg 180).

As unbiblical as it was, in the middle ages, it became the ground for a whole economic system. Continuing with MacCullough:

Already by the ninth century, western church buildings (unlike those in the east) were being designed or adapted for a large number of altars so that priests could say as many Masses as possible for the sake of dead benefactors, or for benefactors with an eye on their coming death – the more Masses, the better. … By the twelfth century, western Christians were taking further this idea of intercession for the dead in the Mass; they developed a more sophisticated geography of the afterlife than was presented in their biblical foundation documents. The New Testament picture of life after death is of a stark choice: heaven or hell. Humanity’s general experience is that such finality ill-matches the grimy mixture of good and bad which makes up most human life.

It was natural therefore for creative Christian thinkers to speculate about some middle state, in which those whom God loved would have a chance to perfect the hard slog towards holiness that they had begun so imperfectly in their brief earthly life. Although the first thoughts along these lines came from eastern Greek-speakers in Alexandria, the idea blossomed in the West, and this place of purging fire, with its eventual entrance to heaven, was by the twelfth century given a name – Purgatory. Further refining of the system added a ‘Limbus infantium’ for infants who had not been baptized but who had no actual sin to send them to hell, and a ‘limbus Patrum’ for the Old Testament patriarchs who had had the misfortune to die before the coming in flesh of Jesus Christ, but these two states of limbo were subordinate to what had become a threefold scheme of the afterlife. Such theological tidy-mindedness suggests that there is something to be said for the view that when the Latin-speaking Roman Empire collapsed in the West in the fifth century, its civil servants promptly transferred to the payroll of the Western Church.

Latin is a precise language, ideal for bureaucrats; moreover, bureaucrats appreciate numbers as well as neatness. Unlike Heaven and Hell, Purgatory was a place with a time limit; its swansong, when it would be finally emptied of the triumphantly cleansed, was to come at the Last Judgement, but meanwhile it might also encompass individual time limits appropriate to those who had various quantities of sins to purge. If the prayer of the Mass was able to prompt the mercy of God, might not the degree of that mercy be calibrated in precise numbers of years deducted from Purgatory pain?

So the medieval West developed a legally founded and endowed institution intended to regularize the prayer of Masses in saving an individual, a family, or a group of associates: this was the chantry (an English word manufactured from ‘cantaria’, a place for singing, so-called from the convention that all Masses are sung). Some chantry foundations might be temporary and modest, borrowing the services of one priest for a lump sum of money or time limited wage (an obit); others could employ a staff of priests, who needed an elaborate permanent organization, and so formed an endowed association – in Latin, collegium. Oxford, Cambridge and some other medieval universities have preserved a number of de luxe chantry colleges through the Reformation upheavals and expanded their teaching functions at the expense of their primary purpose.

But while the Mass was at the centre of this burgeoning industry of intercession, plenty of other commodities could be traded for years in purgatory – literally traded in the case of indulgence grants. Many theologians, particularly the ‘nominalist’ philosophers who dominated northern European universities from the fourteenth century, cautioned that human virtues were no more than token commodities, which God in his mercy made a free decision to accept from an otherwise worthless humanity, but many ordinary people may not have appreciated that subtlety. The Church told them that there was a great deal of merit available, if only it was drawn on with reverence and using the means provided by the Church (pgs 11-13)

The Sacramental Treadmill

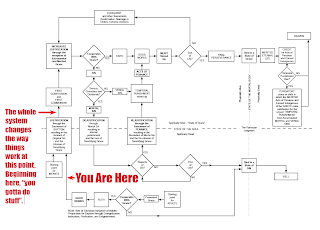

While “the means provided by the Church” may have included some hints toward prayer and “corporal works of mercy” (which the CCC says are “”), the “sacraments”, and especially “the Mass”, provided the real horsepower behind the “get out of purgatory” efforts (see the sacramental treadmill).

I’ll continue with these “developments” at a later time, Lord willing.

Joshua -- a couple of things:

ReplyDelete1. MacCulloch isn't a scholar of Latin; he's a scholar of history - I've given portions of one page out of an 800 page book that covers perhaps 150 years-worth of history. Nobody is making an argument; he's describing history.

2. Why bother even speculating about what Dante might have written? Especially wanting something "scholarly" as you do?

3. The limbus patrum is actually a doctrine that highly magnifies the work and power of Christ

Except that Pope Ratzinger has put out a document that kinda-sorta says "Well, yes, Limbo exists, but it's not needed, because there is "serious theological and liturgical grounds for hope that unbaptized infants who die will be saved and enjoy the beatific vision". http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Limbo

Some more information on MacCulloch:

ReplyDeletehttp://www.theology.ox.ac.uk/people/staff-list/prof-diarmaid-macculloch.html

http://www.amazon.com/The-Reformation-Diarmaid-MacCulloch/product-reviews/014303538X/ref=dp_top_cm_cr_acr_txt?showViewpoints=1

Matthew, thanks for the info.

ReplyDeleteJoshua, I am glad that you are familiar with literature of the period. My purpose in putting up this sort of thing is to provide a public service for Protestant readers who may not have access to MacCulloch or some of the other resources I'm citing. I'm not here arguing for anything at all really.

MaCulloch's statement about Limbo is a throwaway -- it's the only time he mentions it, and in the scheme of things, I simply could have skipped it and it seems as if you'd have nothing to carp about.

You're taking issue with MacCulloch's presentation of things -- you claim, "-I'm writing a comment on a blog post, not a book". Well, MacCulloch DID write a book, and not just any book, but a book that (a) won a price for History, (b) won the British Academy prize, and (c), won a National Book Critics Circle award.

That doesn't make him right, but I would imagine that there was some "peer review" within that process, in which people who know a lot more than you do would have asked him hard questions. So I'm not simply inclined to take your word above his.

The bottom line is that you don't like some of MacCulloch's characterizations. Neither do I, in some cases. But in the vast majority of the work, I'm sure he's extremely reliable. I know that he is not a conservative Christian. But he does a very good job of boiling down some complext concepts into

I just don't accept your notion that he's "offering causes". Where he does so, in passing, he does more thoroughly in other places that I've skipped.

This is, after all, a blog. And MacCulloch does argue a larger point, which I've not gotten to yet. We are still in the back-story.

I'll say again, I'm no fan of the Roman system ...

In case you haven't noticed, I'm a person who thinks that "the Roman system" is not only bad enough "not to be a fan of it", but actively to see it as one of the worst evils in history.

If you read this blog regularly, you'll know that go out of my way to present Roman Catholicism as accurately as possible. In addition to MacCulloch, I also cited the Council of Trent, and I linked to the CCC.

I didn't notice anything out of the ordinary in MacCulloch's presentation. It may not present Limbo in the way that the official Roman Catholic story presents it. But if you listen to everything they say uncritically, you'll end up needing those goggles.