While SJWs fight racist ghosts, structural racism is thriving on the left:

http://www.nationalreview.com/article/450825/dianne-feinstein-jeff-sessions-affirmative-action

Saturday, August 26, 2017

The prince and the pauper

Recently I had an impromptu debate on Facebook regarding the Reformed doctrine of imputation. My exchange alludes to this post as a frame of reference:

This is just a rehash of the hackneyed objection that sole fide is a legal fiction. Is there anything new to say on that issue? What's the point of repeating the stock arguments and counterarguments?

In my experience, debating particular doctrines is never constructive because the participants don't agree on the rules of evidence. For Protestants, it's an essentially exegetical debate over what biblical revelation teaches, using the grammatico-historical method. BTW, contemporary Catholic Bible scholars use the same hermeneutical methodology.

For Catholic apologists, by contrast, it's filtered through selective appeals to the church fathers, the Magisterium, and a priori notions of what is fitting.

The debate over particular doctrines never gets anywhere because that's a downstream discussion where constructive dialogue is only possible if there's common ground on the rules of evidence, which lies upstream.

i) In my experience, many Catholics don't bother to read Bible commentaries (or articles) by contemporary Catholic Bible scholars. If they did, they could avoid the false dichotomy between Catholic and Protestant hermeneutics. There's no essential difference between the way Joseph Fitzmyer, Raymond Brown, Luke Timothy Johnson, John Meier, John Collins et al. exegete Scripture and their Protestant counterparts. The main difference is that Catholic scholars are typically liberal, whereas Protestant scholars range along a liberal/conservative continuum.

ii) I don't have to affirm the general perspicuity of Scripture to say that Scripture is clear on particular issues. For one thing, on certain doctrines, the teaching of Scripture is redundant, so even if a particular word or sentence is ambiguous, it doesn't hang on that.

iii) BTW, Mommy and Daddy didn't teach me that Scripture is perspicuous. My parents didn't have a definitive role in the hermeneutical process in the first place. It would behoove you to avoid stereotyping people if you know nothing about their personal background.

iv) Catholic apologists labor under the illusion that they can achieve the certainty denied to Protestants. But Catholic epistemology simply pushes the same issues back a step. To establish the authority of the Magisterium, you must interpret texts apart from the authority of the Magisterium. If you don't have some confidence in your ability to interpret the church fathers, church councils, &c., then your skepticism disqualifies you from ever making a case for the Magisterium.

iv) I don't fret over inconclusiveness. I accept the epistemic situation that God has put us in. I don't invent a makeweight.

In my experience, modern Catholic Bible scholars as well as modern Catholic church historians compartmentalize their faith from their scholarship. Their scholarship yields one set of conclusions, but they partition that off from their faith. They continue to profess Catholicism despite the results of their scholarship. That's analogous to liberal Protestants.

i) This goes to a fundamental difference in theological method, where you appeal to your philosophical intuitions to veto exegesis. That makes an element of sense if one rejects the revelatory status of Scripture. But it's improper to say I preemptively discount an interpretation that conflicts with my philosophical intuitions even if the best exegetical arguments support that interpretation.

ii) I don't think imputation presumes a theologically voluntaristic view of divine sovereignty, if that's what you're angling at.

iii) I gave hypothetical illustrations in which agent A acts on behalf of and in place of agent B, so that agent B acquires an ascribed status by virtue of what was done for him that's functionally equivalent to an achieved status. That's not unique to Protestant/Reformed theology. That's a commonplace in social interactions. Although my examples were hypothetical, they have many real-world counterparts. So even at the level of philosophical intuitions, there's nothing counterintuitive about it.

iv) Another potential problem is that many Catholics frame these issues in terms of Thomistic metaphysics. At best, the objections are only cogent if one grants all the paraphernalia of Thomistic metaphysics.

Notice that I cast the issue, in part, by reference to standard sociological categories (achieved/ascribed status) rather than metaphysical categories.

"1) I don't think scripture allows for a multitude of different metaphysical positions, for one thing. I think it constrains us when we do our exegesis."

What constrains exegesis? Metaphysical positions that Scripture rules out, or metaphysical positions (criteria) we bring to Scripture, apart from Scripture?

"And you appear to be saying that I'm using philosophy to veto your exegesis"

That's manifestly the case.

"And you appear to be saying that I'm using philosophy to veto your exegesis when I'm simply saying that you're exegesis in my exegesis both involve different philosophical frameworks that we should not ignore."

And what distinctive philosophical framework do you think is driving my distinctive interpretation?

"If your framework is conjoined to your exegesis and your framework is wrong then your exegesis is wrong, too. The same applies to mine."

You haven't identified what framework I've conjoined to my exegesis. You've also indicated that there's something uniquely Protestant about my approach, but that's not the case. For instance, as Eleonore Stump has said in a different context:

"If one passage can be set aside because it strikes us as incompatible with our moral intuitions, then others may have to be treated in the same way. But then our moral intuitions will be the standard by which the texts are judged, and the texts can’t function as divine revelation is meant to function, as a standard by which human beings can measure and correct human understanding, human standards, and human behavior." "The Problem of Evil and the History of Peoples: Think Amalek." M. Bergmann, Michael J. Murray, and M.C. Rea., eds. Divine Evil? The Moral Character of the God of Abraham (Oxford University Press 2011), 181.

The same holds true for setting aside an interpretation because it strikes you as incompatible with your philosophical intuitions–even if that interpretation has the best of the exegetical arguments.

Your position reminds me of my many debates with unitarian philosopher Dale Tuggy. His metaphysical criteria preemptively discount the possibility that Scripture teaches the deity of Christ.

"If you don't think it presumes that, I'd like to hear an explanation as to what view of divine sovereignty you feel it does involve."

You seem to think the Reformed doctrine of imputation presumes a voluntaristic or Cartesian notion of divine omnipotence. But that's generated by what happens when you plug imputation into your (Thomistic?) metaphysical scheme. I'm not operating with your metaphysical framework (whatever that is). It's up to you, not me, to explicate why you think imputation generates that consequence, inasmuch as that's based on your understanding rather than mine.

"Do you hold the son's friend is truly being treated as the son in an interchangeable way that isn't based on ontology? The father has to realize he is still just a friend and isn't conflating. Obviously the privilege wasn't so exclusive in the first place."

He receives a benefit which the father would normally reserve for his own son. He's not treated "as" the son but "as if" he's the son. No, it's not based on ontology. Sure, he's still just a friend and not the son. That's the point. In the nature of the case, vicarity isn't identity. Not ontological identity, but functional equivalence.

"As for adoption, I view it ontologically. It certainly is when Scripture talks about us as sons and relates it to our being born again - Christ gets called only-begotten not because that terminology od being begotten can never be applied to us, but because he is so eternally and we are so temporally, hence the semantic distinction. But I'm not a child of God for primarily legal reasons - the designation reflects the ontological reality and does so necessarily (and it seems to me that your metaphysics cannot allow for that since the morally innocent Christ is legally guilty on the cross). In the case of human adoption I entirely view the process of the state calling someone an adopted child as secondary or contingent."

i) To begin with, you're inventing a generic concept by merging different Bible writers like Paul and John, as if their positions are interchangeable or reducible to a common denominator. But each one has his own paradigm. John prefers a reproductive metaphor while Paul prefers an adoptive metaphor. One involves an analogy with biological sonship while the other involves an analogy with adoptive sonship, which, by definition, is not biological. You're blurring an essential distinction between the two.

ii) BTW, while I affirm the eternal sonship of Christ, I reject eternal generation. But that's an argument for another day.

"Similarly, if the state pronounces someone guilty or innocent it needs to align with "the truth of the matter" about the person, that is to say the MORAL innocence or guilt. It's absolutely counterintuitive for us to say that a court could declare someone legally innocent who is morally guilty or declare someone legally guilty who is morally innocent. Moral guilt and innocence is the thing that most people give a damn about and they expect any legal determination to necessarily reflect it or it is a worthless lie."

It's that attitude which renders Catholics impervious to the Gospel. Paul in particular stresses the prima facie dilemma of how God can justly forgive sinners. A just God is supposed to punish sinners.

Sinners are guilty before God. So how can they be acquitted? How can a just God save anyone if everyone is sinful? That's the conundrum. Paul resolves that dilemma by appeal to vicarious atonement and penal substitution.

"And you might think that that means that the thing I said is counterintuitive (and it certainly is in every other occurrence)"

The vicarious principle is common in human experience.

"so that their new legal status is a direct reflection of their ontological, moral status."

Even making allowance for sanctification, they remain sinners.

"You want me to hold that he legally declares ungodly men righteous and sure, is simultaneously morally conforming them to that, but I see that as taking the declaration itself in a rather literal and univocal way."

No, I'm taking that in a substitutionary way.

"And I think the twofold distinction between legal and ontological/moral in the Protestant paradigm creates problems for knowing what specific verses are talking about, justification or sanctification."

Paul repeatedly and emphatically denies that one can be justified by works (or works of the law). In his scheme, justification and works are antithetical principles. He's the one who "radically distinguishes" the two.

"As for adoption, I view it ontologically."

My comparison was more specific. I used adoption to illustrate the distinction between achieved status and ascribed status. A king can adopt a peasant. That instantly elevates the peasant's social standing. He becomes the crown prince and heir apparent not on account of anything he did, but on account of something done for him. It's as if he was the conqueror who founded the kingdom by his military exploits. For the conqueror, that's achieved status. Yet the adoptive son enjoys the equivalent status despite having done nothing.

In fact, that's true for biological sonship. You are born into a social status. You may inherit the family fortune. You did nothing to earn it.

"For me the issue isn't whether you earned it or not. The issue is whether it is an ontological reality or if it is merely something nominally describing you. As in to me the issue isn't how my brown desk got brown; the issue is that it is completely meaningless to give it the 'status' of being brown or participating in brown-ness unless you are talking about its real participation in that quality. I don't divide the universe into, say, legal brownness vs real brownness."

You're recasting the issue in your preferred metaphysical categories. That's your prerogative, but I don't grant your conceptual scheme as determinative. Moreover, I don't regard justification as analogous to color predications.

"With regards to the adoptive son focusing on how he got adopted or on questions of who meriting that are entirely besides the point. The Sixth Session of Trent makes it clear that we don't earn our justified status in the first place."

To my knowledge, traditional Catholic theology bifurcates justification into first justification without works and second justification involving congruently meritorious works.

"The issue is whether or not that status is merely reflective on an ontological reality or if it is something else altogether."

You keep insisting that justification must conform to your strictures, but that's imposing your preconception on Pauline categories. In Pauline theology, God justifies sinners. They are not "ontologically" righteous. They are the opposite of "ontologically" righteous.

"Would you say that the Crown Prince did the military exploits 'legally'?"

I'm not using that framework. The crown prince didn't perform the military exploits at all. Rather, he's the beneficiary, as if those were his personal attainments.

Your approach reminds me of methodological atheism. Even if divine agency is the correct explanation for a particular phenomenon, the methodological atheist discounts that explanation in advance. By the same token, your approach disallows imputation even if it turns out that in fact this is what Paul really means. You have a screen in place that filters out certain interpretations even if they happen to be correct. Is there any kind of evidence you'd allow to count against your interpretive grid, or is that unfalsifiable?

Game of Thrones

This is a sequel to my prior post:

1. Game of Thrones (hereafter GOT), which has occasioned so much debate, was hovering in the background of my post, but I didn't comment on the series, and my position can't be inferred from my post.

There are lots of articles about "Should Christians watch Game of Thrones"? I've skimmed a number of these articles, which didn't affect my own position. Some social conservatives like David French and Ben Shapiro defend it while critics like John Piper, Kevin DeYoung, and Matt Walsh deride it.

It may not be coincidental that French is a former Marine.

From what I can tell, religious pundits roughly subdivide into regular viewers who defend it, those who attack it unseen, and those who attack after having sampled it.

2. There is nothing necessarily wrong with prejudging something based on secondhand information. I will never watch The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, The Hills Have Eyes, or the Saw series. A synopsis or movie review can be sufficient to form a preliminary judgment about whether that's suitable viewing.

However, it does put critics like Piper and DeYoung at a certain disadvantage, inasmuch as they can't be very specific about what's wrong with the series.

For the record, I watched the first two seasons, then bailed. If I had it to do over again, I wouldn't watch it at all. I could say the same thing for some other movies I've seen. Occasionally I start a movie or TV episode, then stop before I see it all, because I just don't like what I've viewing.

To say I wouldn't do it again isn't an admission of guilt. It's one of those dilemmas where you don't always know in advance what to expect. In the case of GOT, I was curious what all the fuss was about.

3. So why did I drop out after two seasons? Critics focus on the "pornographic" material, but before we get to that, there are other problems. It's not like I think GOT is a firstrate drama if only we could edit out the sex scenes. Rather, I think fans greatly overrate the dramatic quality of the show.

It's not that GOT is bad from a dramatic standpoint. To judge by the first two seasons, it's a cut above much TV fare. But in my opinion, fans who defend GOT because they think it's so outstanding unwittingly reveal their lack of sophistication. At a purely artistic level, there are much more intelligent dramas. La Femme Nikita (1997-2001) was much more intelligent. Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy (1979) was much more intelligent. The (underrated) reboot of The Prisoner (2009) was much more intelligent. Fans of GOT would be bored by dramatic excellence.

I don't say that as a general putdown. I don't judge people by their artistic taste. On the one hand there are saintly believers with kitschy taste. Take devout Christians who buy Thomas Kinkade. By the same token, Michael Brown recently used schmaltzy 50's fare like Lawrence Welk, I Love Lucy, and Lassie Come Home as his standard of comparison. To each his own.

On the other hand, there are degenerates with impeccable taste. Anthony Blunt was an eminent art historian. In addition, he was a raging homosexual, KGB recruiter, and the architect of the Cambridge spy ring. To be a world authority on Poussin doesn't make you virtuous. He was vile. But I am critical of people who flatter themselves by defending GOT on artistic grounds, when their defense betrays them to be far less discriminating than they fancy.

4. From what I saw, GOT basically reflects pagan morality and pagan mythology. It's a fairly accurate depiction of how pagans behave. It reminds me of I, Claudius (1976), which was superior to GOT. GOT depicts the old Roman virtues as well as the old Roman vices.

One reason I didn't stick with GOT is that it has too few admirable characters. And the prevailing worldview is nihilistic. There is no eschatological justice, so there's no incentive to be virtuous. I don't object to depictions of evil, but I prefer a redemptive context. Not wallowing in evil. Not evil for evil's sake.

5. It's fatuous to defend GOT on the grounds that Christians need to be in touch with the evils of a fallen world. No doubt. But you don't need to read or watch fiction to know about evil. The daily news provides saturation exposure. Not to mention personal experience.

That doesn't mean we should avoid dramas that unsparingly depict evil. But there's plenty to choose from. And there are better examples than GOT.

6. Christian critics generally accentuate the sex and nudity. I'll get to that, but their emphasis lacks balance. As I recall, GOT opens with a graphic decapitation scene. Why don't Christian critics have more to say about "gratuitous violence"? Maybe it's just because most of them haven't actually seen it, so they can't single out specific scenes.

I don't think we can say anything worthwhile about cinematic violence in general. Whether that's justifiable or unjustifiable is context-dependent. There's a difference between "gratuitous" violence and violence that serves a dramatic function. It depends, moreover, on the vehicle. Take a film with a redemptive theme like To End All Wars (2001).

7. Then there's profanity. GOT uses a certain amount of profanity. That's realistic, but I don't care for the profanity. It's not that I consider profanity to be inherently objectionable. It's just that if I don't like the story in which violence or profanity is embedded, then there's nothing to mitigate the violence or profanity.

To take a comparison, Ordinary People (1980) tells the story of a family falling apart after one son died in a boating accident. It depicts the different coping strategies of the survivors: mother, father, brother. There's a certain amount of profanity between the brother and his classmates. I don't have a problems with that because it's fitting in context, and the story is a good story. But GOT lacks those compensatory virtues, so I don't have the same indulgence.

8. What about the sex and nudity? I don't think artistic nudity is intrinsically objectionable. Take Rodin's The Kiss. That's erotic art, but it's very tasteful. A common grace celebration of God's gift of sexuality. There can be ennobling as well as ignoble representations of sex and nudity. Although pornography and erotica overlap, they are sometimes distinguishable, and they ought to be distinguishable. Botticelli's Birth of Venus is another case in point.

By contrast, Rodin's Eve is not erotic, but tragic. Ghiberti's Adam and Eve panel is a reverent and dignified representation of the first couple in Gen 2-3.

In one of the early episodes, possibly the pilot episode (I forget), there's a scene of Daenerys Targaryen emerging from her bath. It's like female nudes in Western art.

There's a difference between nudity and a sex scene. There's no simulated sexual intercourse. It's just the image of a beautiful female nude. Unless you think the human body is an inherently unsuitable subject for artists to admiringly portray, I don't think that, in itself, is objectionable. Sex appeal isn't intrinsically degrading. Heterosexual appreciation for the body isn't intrinsically degrading. So I wouldn't classify that particular scene as pornographic.

Mind you, the nudity in GOT is intentionally pornographic, in the sense that the director and producers are using that as a come-on. But depending on the context, their intentions are separable from what is shown in its own right.

However, I think this scene is exceptional in that regard. I'd say most-all of the other nude scenes are pornographic.

9. Let's take another example: in one of the episodes, Bran is crippled after he's thrown out a window, when he was caught spying on Cersei and Jaime having incestuous intercourse.

In theory, the sex scene could be justified on the grounds that one thing leads to another. Bran likes climbing. He was climbing the tower when he saw Cersei and Jaime in flagrante delicto. To dispose of the witness, he's hurled from the tower. He survives, but is crippled by the fall. But as compensation, he develops second sight. So there's a certain dramatic logic to it.

However, that's a weak justification. To begin with, he needn't be pushed to fall. He could accidentally fall when climbing. It's naturally hazardous to climb up the tower.

And what, really, is the point of seeing Cersei and Jaime have sex, much less incestuous sex? Even if Bran's a tattletale, yet given the prevailing social mores of GOT, is there anything scandalous about Cersei and Jaime? Do they have a reputation to preserve? The social world of GOT is awash is decadence.

Labels:

Art,

ethics,

film criticism,

Hays,

Pastoral Issues,

Television

Wesley So: Elite US Chess Player Shares His Christian Faith

Christianity is the “thinking man’s religion”.

|

| Wesley So: a Christian and the #2-rated chess player in the world |

I was 12 when Bobby Fischer played Boris Spassky and won the World Championship title – and I was heartbroken when he refused to play Anatoly Karpov in the next World Championship cycle, and consequently the World Chess Federation (“FIDE”) stripped him of the title. These days, I play chess informally, and someone even talked me into playing in a league, which I greatly enjoyed.

CT enabled Wesley to publish a first-hand account of his conversion to Christianity and his Christian life:

By the end of 2014, I had quit college, moved in with my foster family, and launched a professional chess career. Most importantly, I had also entered into a relationship with Jesus Christ. It all happened so fast that we still look back at those early days in disbelief.

Since my foster parents were mature Christians, it must have been obvious when I first moved in that my faith wasn’t as sophisticated as theirs. They never condemned me for this, but they did insist that living as a member of the family meant abiding by certain house rules and customs. I would need to read my Bible every night and faithfully accompany them to church on the weekend. Over the first few months, I would fall asleep during every sermon—not because they were boring, but because all the changes in my life were so stressful and overwhelming.

I never minded going to church, and somehow I managed to absorb real wisdom from those sermon fragments. I also got very interested in reading the little Bible I was given. Whenever I had questions I would ask my foster parents, and their answers were always simple and made good sense. They taught me how to find answers in the Bible myself and use it to check what others said. The Bible was the final authority, deeper and wiser than the internet and more truthful than any of my friends.

Before long, I was practicing my faith in a more intense way. My new family calls Christianity the “thinking man’s religion.” They encouraged me to ask questions, search for answers, and really wrestle with what I discovered. All the while, I would observe how they lived their lives, taking note of how they spent their time and money. They worked hard, they always went the extra mile to help others, and they made every effort to resist immorality. I knew I wanted the kind of simple, contented, God-fearing life they enjoyed.

The God of Everything

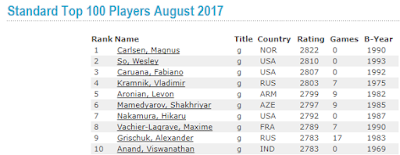

Current Top 10 Chess Players in the World

People in the chess world sometimes want to know whether I think God makes me win matches. Yes. And sometimes he makes me lose them too. He is the God of chess and, more importantly, the God of everything. Win or lose, I give him the glory. Of course, it’s hard when I don’t get what I want, the way it is for any child whose father says no. But even when I don’t understand God’s ways, I’m confident that his vision is much bigger than my own.

Instead of worrying about the future, I try to focus on the work God has put before me. Right now it’s chess, so I study it diligently and play it as well as possible. Will I rise to become the world champion one day? Only God knows for sure. In the meantime, I know that he is a generous and loving father, always showering me with more blessings than I could possibly deserve. I content myself with playing one match at a time and practicing gratitude for my daily bread.

Born in 1993, he’s as old as my #3 son. But Wesley So has as good a chance as anyone of becoming the next World Champion.

Read his whole story here.

Here’s a link to the list of the Top 100 chess players in the world.

Here’s a link to Wesley So’s historical rating and ranking.

Friday, August 25, 2017

Deathbed prayer

i) I think some well-meaning Christians are confused about how to pray for the disabled, terminally ill, degeneratively ill, and other suchlike. They pray for miraculous healing, and that's well and good. We should pray for miraculous healing. And sometimes God grants our request.

Problem is, some Christians think that's the only kind of prayer we should offer in those cases. Even though we know that God doesn't always answer such prayers, indeed, that God rarely answers prayers for miraculous healing, they seem to think it would be faithless to pray for anything short of miraculous healing. That's giving up!

One problem with their attitude is that it's possible to pray for more than one outcome. In addition to your preferred outcome, you can have a contingency prayer. You can pray for what you hope will happen, but you can have a fallback request in case that doesn't happen. You can say something like: "God, I pray that you will heal so-and-so of his terminal illness, but if not, I pray that you will grant him a peaceful death".

ii) Moreover, to only pray for healing can injure the faith of those we pray with. I knew a blind couple. Both husband and wife were born sighted but lost their eyesight in adulthood. The wife later died of diabetes (or complications thereof).

She shared with me her frustration about well-meaning Christians who, upon first meeting her, always wanted to pray that God restore her sight. "Don't you want God to heal you?" "Do you have faith?"

Imagine how discouraging it would get to have people constantly pray with you for healing, but nothing happens. They never let you come to terms with your condition.

iii) Apropos (ii), you can pray for someone without praying with them. While it's often good to pray with someone, if you have direct contact, there are situations where it's more tactful to pray for them without their knowledge. That way they can't be disappointed if the prayer goes unanswered.

iv) To adapt an illustration that Lydia McGrew recently used, suppose I live in tornado alley. Should I take the precaution of building a root cellar to protect my family in case a tornado strikes, or would that be faithless?

Or suppose I buy home that already has a root cellar. If I see a twister making a bee line for our house, should we head for the root cellar, or would that be faithless? After all, God has the power to divert the twister or make it instantly dissipate. Are we distrustful if we don't wait to see if God will miraculously intervene to spare us from the tornado? Should we wait until it's too late to take refuge in the root cellar?

Yet we know from experience that God doesn't always or even generally deflect natural disasters in answer to prayer. Is it faithless to take ordinary providence into account? Is it faithless to have a backup plan? After all, God didn't promise to save us from the twister.

iii) Finally, I ran across a statement today that reminds me of something I've said: Some Christians "campaign" to get as many people to pray about something as possible...seem to have a kind of theology of "votes" - if God's side gets enough votes, then the person who is ill (for example) is healed, but the person is not healed if not enough votes can be solicited.

Labels:

Hays,

Miracles,

Prayer,

Providence

Thursday, August 24, 2017

Singer on Antifa

Hard leftist Peter Singer on Antifa:

https://www.project-syndicate.org/print/antifa-violence-against-racism-by-peter-singer-2017-08

https://www.project-syndicate.org/print/antifa-violence-against-racism-by-peter-singer-2017-08

Labels:

Donald Trump,

Hays,

Peter Singer,

Politics

D. James Kennedy Ministries Sues SPLC over Hate Map

This will be one to watch.

A venerable Christian ministry based in Fort Lauderdale recently saw its name listed on a CNN map of “all the active hate groups where you live,” as well as in local news reports as the No. 1 hate group in Florida.

D. James Kennedy Ministries shares sermons, devotionals, and religious liberty messages inspired by the late founder of Coral Ridge Presbyterian, a prominent Florida megachurch. In media coverage after Charlottesville, the Christian broadcaster was mapped alongside about 60 “hate groups” in the Sunshine State, using designations from the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC).

“Enough is enough,” said Frank Wright, president of D. James Kennedy Ministries, which filed a lawsuit against the SPLC on Wednesday. The organization also sued GuideStar and AmazonSmile for their use of the SPLC list.

Conservative Christian organizations have challenged the SPLC’s “anti-LGBT” category for years, but Wright’s is the first to take legal action—spurred by the controversial watchdog group’s increasingly vocal activism during Donald Trump’s presidency. The SPLC recently received a prominent boost from Apple, which pledged a $1 million donation and will launch a new feature to allow users to donate directly from iTunes.

Beach preaching

1. There's been an explosion of Christian material on pornography. But from what I've read, there's a lack of clarity in how the issued is delineated. Many of the stock arguments are weak arguments. In fairness, people can sometimes instinctively sense that something is wrong, even though they don't have a readymade arguments at their fingertips. But some sifting is in order. If you use bad arguments, there are people who can see through bad arguments, and that's counterproductive.

Admittedly, I haven't done in-depth study of the issue. It doesn't interest me that much. And there's such a plethora of material on the subject in Christian circles that it's hard to know where to start to derive a representative sample of the arguments.

Labels:

Andy Naselli,

ethics,

Film,

Hays,

hermeneutics,

John Piper,

Pornography,

Television

Wednesday, August 23, 2017

Faith is waiting

The Reformed definition of saving faith traditionally has three elements: knowledge, belief (or assent), and trust.

However, trust is a forward-looking disposition. The past can't be an object of trust, because, for better or worse, that's over and done will. It can't harm you anymore. The future is potentially threatening in a way the past is not. So trusting God is future-oriented. By contrast, knowledge and belief are applicable to past and future alike.

On a related note, to a great extent faith is synonymous with waiting. Not in reference to the past, obviously. You can't wait for the past. That's come and gone.

But in reference to the future, faith is synonymous with waiting. A certain kind of waiting. Expectation. Or hoping for the best.

We wait for God's promises to come due in our lives. Ultimately, at the moment of death.

Faith can be fatiguing in the way that waiting can be fatiguing. That involves psychological time. Time flies when you're having fun, but time drags when you are waiting.

Psychological time is impacted by deadlines, or their absence. Take a wedding date. That fosters a mounting sense of anticipation.

By contrast, part of what makes an ordeal onerous is if there's no end in sight. If you knew when the ordeal was going to end, it might be easier to take. You could pace yourself.

But it's harder to cope when there's no indication that it will end anytime soon. When it drags on indefinitely.

Sometimes in life we know when we reached a turning-point. The worst is behind us–at least in that regard. Things should be better from hereon out–at least in that regard.

However, some turning-points in life are invisible. Things will start getting better. Or we're reaching our goal. Yet we don't know that in advance. It may be just around the next bend or over the next hill, but we can't see it. There will be a day or week when we do everything for the last time, although we may not know it.

Faith is waiting, and waiting can be trying. It may be an effort to get through each day, then you have start all over again the next day.

That's one of the nice things about death. However bad your ordeal, it will end. You'd prefer it to end sooner, but it may end later. Nevertheless, it will come to an end. And that's what makes waiting bearable. Except for the damned!

Antifa At Laguna Beach

Labels:

Culture Wars,

Donald Trump,

Hays,

news,

Politics

Alien abduction stories

An atheist trope is to cite alien abduction stories to cast doubt on the reliability of testimonial evidence. There are, however, several problems with his comparison:

1. An atheist depends on testimonial evidence to even be aware of alien abduction stories.

2. Unless a Christian happens to be an expert on ufology, he has no informed opinion to offer on alien abduction stories. Ufology is a study unto itself. A huge swamp.

3. In addition, the comparison suffers from a basic equivocation. In assessing alien abduction stories, we need to differentiate actual eyewitnesses to something from people who fraudulently claim to be eyewitnesses. Not everyone who claims to be an eyewitness is in fact an eyewitness. Sifting testimonial evidence requires us to distinguish between people who simply make stuff up from actual observers.

When the reliability of testimonial evidence is challenged, what is being challenged? The credibility of a witness to be an actual witness? Or the accuracy of his perception, recollection, and/or interpretation of the experience?

4. To take a comparison, suppose someone claims to be an eyewitness to the sinking of the Titanic, assassination of Bobby Kennedy, or demise of Jack Ruby. In that case, we have independent evidence that there was something to be observed. Evidence that the Titanic, Jack Ruby, and Bobby Kennedy existed.

But the evidence for alien abductions is circular inasmuch as reports just are the putative evidence that extraterrestrials are kidnapping humans. Yet there can only be alien abductions if extraterrestrials exist. They can only be observed in case they exist. So what's our basis to classify these reports as eyewitness testimony? There can only be observers if there's something to observe.

Tuesday, August 22, 2017

Hellfire

Then he will say to those on his left, 'Depart from me, you cursed, into the eternal fire prepared for the devil and his angels' (Mt 25:41).

Traditionally, the fiery imagery for hell is regarded as a metaphor for the punitive psychological pain and suffering which the damned experience. And that may be correct.

Insofar as the damned are raised to life, it might possibly include punitive physical pain as well.

However, fire, and other synonyms, can have a different figurative meaning. For instance:

But if they cannot exercise self-control, they should marry. For it is better to marry than to burn (1 Cor 7:9).

There it denotes sexual passion. "To burn" can mean "to yearn ardently" for something. So the imagery of hellfire might symbolize punitive frustrated longing.

Labels:

Damnation,

Hays,

Hell,

hermeneutics

Believe truth! Shun error!

From a recent Facebook debate I had with an atheist:

Your objection is deeply confused. You act as if his credibility is relevant. It's not. Credibility is important in a witness. But he isn't asking anyone to simply take his word for what he says. His personal motives are beside the point. All that's germane is the quality of argumentation and evidence he presents in support of his position, and not whether you trust the purity of his motives.

You are still fixated on motives rather than evidence, which is a red herring. In addition, that objection cuts both ways. What about atheists who say that even if they directly witnessed an apparent miracle, they'd believe that was a hallucination before they accepted that as evidence for God?

What about atheists who say the God of the Bible is evil? Haven't they burned their bridges for believing in God regardless of the evidence?

And I've explained why your obsession with motivations is a decoy. For instance, the general purpose of formal public debates is not for one debater to convince the other, or vice versa. Rather, it's for the benefit of the audience. Both speakers are representatives of certain viewpoints. The point is to engage their arguments, not because the speakers are sincere, but because they are capable exponents of a position you wish to evaluate. I've seen and read many debates between Christians and atheists. I don't evaluate the performance by speculating on the sincerity of the atheist. I just consider the quality of his arguments.

BTW, from a secular standpoint, why does it even matter what motivates someone's beliefs? From your viewpoint, Christians and atheists share a common oblivion when they die. Nothing they believe makes any ultimate difference to them or the world at large. What difference does, from a secular standpoint, if a Christian's motives were pure or impure? The morgue doesn't differentiate between the corpses of Christians and atheists.

You said "I don't think there's anything that I could read in a book that could convince me that a God exists." That's unqualified skepticism.

Is that your position about history books in general? Sometimes we must sift between conflicting historical sources. Does that mean we should be skeptical about history in general? So you're skeptical about the existence of Lincoln, the Crusades, the Battle of Waterloo, &c.?

Most of what you believe is based on secondhand information. Why do you demand firsthand experience in the case of God's existence? Why do you have a different standard of comparison for the historical Charlemagne than the historical Jesus?

The Gospels are arguably 1C historical accounts of a 1C historical figure, based on eyewitness testimony. Are you suggesting the sources are comparable for the existence of Vishnu?

Is Vishnu empirical in the sense that Jesus is empirical? In addition, not all concepts of the divine have the same explanatory power.

So your claim is that reported miracles are inconsistent with observed reality. But that's circular inasmuch as observers report miracles.

To disbelieve all reported miracles assumes extreme skepticism about testimonial evidence. Yet you admit that you rely on testimonial evidence.

You have yet to address the vicious circularity of your objection. What we know about reality is based mostly on observational claims. Well, that includes reported miracles.

Moreover, this isn't even a case of conflicting observational claims. The fact that some people don't observe miracles doesn't logically contradict other people observing miracles.

if your comment was alluding to the ascension of Elijah, he didn't ascend to heaven on a winged horse. Perhaps, though, you were alluding to Muhammad's night journey. If so, that depends on the credibility (or lack) thereof, of Islam–and Muslim sources generally.

It's funny how often atheists act as if non-Christian miracles are inconsistent with the Christian worldview. Atheists have a bad habit of parroting stock objections by other atheists.

Your question is confused. Verifying a miracle is a separate issue from the patient's conviction that Vishnu performed it. This goes back to your irrational fixation with motives.

You keep conflating two distinct issues. A verified miracle disproves naturalism.

Moreover, you retreat into hypotheticals about the Hindu woman. That becomes another diversion. Instead of addressing actual, well-attested case studies, you retreat into imaginary what-if scenarios. Why don't we begin with reality rather than counterfactuals?

For starters, you need to produce a Hindu with a verifiable miracle before we even address the question of divine attribution. You keep putting the horse before the cart. There's extensive documentation for Christian miracles. This is a problem with atheists who think that can just wing it by resorting to fact-free hypotheticals. There's a place for hypotheticals, but that's not a substitute for evidence.

"Let me ask you this: If you heard a Christian say she experienced something that would fit the definition of a miracle"

You have a bad habit of recasting the issue as a string of vague claims. But I'm not discussing highly ambiguous examples. You need to acquaint yourself with specific evidence for specific examples.

You play the typical game of stipulating an artificial test for miracles. But that reveals a complete misunderstanding of where the onus lies. Naturalism denies miracle in toto. That's a universal negative. All that's required to falsify a universal negative are a few verifiable counterexamples.

The logical and honest approach is to establish that a miracle has occurred. That rules out atheism at one stroke. That's the first step. Anthony evades that by shifting the discussion to hypothetical rival divine candidates. And he keeps harping on that as if it rules out verification of a miracle. A bait-n-switch.

Regarding the Vishnu hypothetical:

i) On the one hand, the Christian God might have occasion to answer the prayer of a Hindu. Suppose a linear ancestor of Ravi Zacharias is deathly ill. Even he dies, Ravi will never exist. The Christian God might answer a Hindu prayer so that further down the line, Ravi will be born.

ii) On the other hand, suppose, for discussion purposes only, that Vishnu is real. Suppose he sometimes answers Christian prayers. Christians are praying to the wrong god, but have no way of knowing that. Not only are they mistaken, but they're in no position to detect and correct their mistake.

Is that thought-experiment supposed to be a defeater for Christianity?

Let's consider another thought-experiment: suppose the devil plants fossils to make people go to hell by losing their faith in Scripture. Atheists mistakenly believe in naturalistic evolution because the devil planted false evidence. Is that hypothetical a defeater for atheism? Can Magnabosco disprove the thought-experiment?

Another basic problem with your tactic is that it cuts both ways. If he's going to cast the issue in terms of case-by-case elimination of rival gods, how does he, as an atheist, propose to dispatch the "330 million" gods of Hinduism, as well as other theisms, polytheisms, pantheisms, and panentheisms?

In my experience, many atheists act as if the worst consequence is to mistakenly believe Christianity. But why is that worse than mistakenly refusing to believe in Christianity or mistakenly believing in atheism?

Suppose, for argument's sake, people mistakenly believe in Christianity. What do they have to lose? If atheism is true, when they die they never find out they were wrong because they instantly pass into oblivion. And when atheists die, they never find out that they were right, because they instantly pass into oblivion.

By contrast, suppose people mistakenly refuse to believe in Christianity. What do they have to lose? Everything!

As William James put it, in his classic essay ("The Will to Believe"):

ONE more point, small but important, and our preliminaries are done. There are two ways of looking at our duty in the matter of opinion,--ways entirely different, and yet ways about whose difference the theory of knowledge seems hitherto to have shown very little concern. We must know the truth; and we must avoid error,- -these are our first and great commandments as would-be knowers; but they are not two ways of stating an identical commandment, they are two separable laws. Although it may indeed happen that when we believe the truth A, we escape as an incidental consequence from believing the falsehood B, it hardly ever happens that by merely disbelieving B we necessarily believe A. We may in escaping B fall into believing other falsehoods, C or D, just as bad as B; or we may escape B by not believing anything at all, not even A. Believe truth! Shun error!-these, we see, are two materially different laws; and by choosing between them we may end by coloring differently our whole intellectual life. We may regard the chase for truth as paramount, and the avoidance of error as secondary; or we may, on the other hand, treat the avoidance of error as more imperative, and let truth take its chance. Clifford, in the instructive passage which I have quoted, exhorts us to the latter course. Believe nothing, he tells us, keep your mind in suspense forever, rather than by closing it on insufficient evidence incur the awful risk of believing lies. You, on the other hand, may think that the risk of being in error is a very small matter when compared with the blessings of real knowledge, and be ready to be duped many times in your investigation rather than postpone indefinitely the chance of guessing true. I myself find it impossible to go with Clifford.

In praise of unanswered prayer

Much is written about the "problem of unanswered prayer", but there's a flip side to that. It means we're not ultimately responsible for getting answers to prayer. God answers some prayers while leaving other prayers unanswered, and it's not up to us which is which. If a prayer goes unanswered, it's not necessarily or even generally because we failed in some way, although, as James explains, there can be impediments to prayer (e.g. faithless prayer, ill-motivated prayer). When I pray, I'm not in control. The results are entirely in God's hands. If the prayer goes unanswered, or appears to go unanswered, that may be disappointing, but it's nothing to fret over. We might fret over our circumstances, but there's nothing more we could have done or should have done to ensure an answer. We can't make God gives us what we request. And that's a relief. That takes the weight off my shoulders. It means it's not our fault if the prayer goes unanswered. No one's to blame. Not God. Not the supplicant. It's just that God, in his wisdom, chose not to grant our request–for reasons we may never understand in this life.

Labels:

Hays,

Prayer,

Providence

A Brief History of Reality (as it relates to the culture wars of our times)

I’m not trained in philosophy, by any stretch, although I’ve done some reading on the topic. As well, I’m not a sociologist, nor even a close observer of contemporary culture, but I do live here and observe things.

And so I publish this blog post with the idea of starting a discussion that is looking forward to diagnosing some of the cultural difficulties that we face today, and not because I’m not suggesting I have all the answers. As I’ve mentioned in the past, I see myself as more of a journalist, a reporter (but an honest one), collecting information and passing it on, than anything else.

The study of “reality” may be found within the fields of “metaphysics” and “ontology” (with the differences between them viewed as):

While there are many complexities within these discussions, in broad outline form, the history of “reality” has kind of followed this trajectory:

And so I publish this blog post with the idea of starting a discussion that is looking forward to diagnosing some of the cultural difficulties that we face today, and not because I’m not suggesting I have all the answers. As I’ve mentioned in the past, I see myself as more of a journalist, a reporter (but an honest one), collecting information and passing it on, than anything else.

The study of “reality” may be found within the fields of “metaphysics” and “ontology” (with the differences between them viewed as):

Metaphysics is a very broad field, and metaphysicians attempt to answer questions about how the world is. Ontology is a related sub-field, partially within metaphysics, that answers questions of what things exist in the world. An ontology posits which entities exist in the world. So, while a metaphysics may include an implicit ontology (which means, how your theory describes the world may imply specific things in the world), they are not necessary the same field of study.

While there are many complexities within these discussions, in broad outline form, the history of “reality” has kind of followed this trajectory:

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)