I’m on record as having said that I don’t like the word “catholic” (and its variations “catholicism”, etc.), especially not as it applies, for example, in the phrase “Reformed Catholicism” etc. There are too many different definitions of the word, and there is too much opportunity for confusion. Roman Catholicism, for sure, hangs onto that title “Catholic” – equivocating from when it was used in the Niceno-Constantinopolitan creed (“one holy, catholic, and apostolic church”) until its use after the Council of Trent. It is supposed to represent “early beliefs”, but the weight of evidence is showing that even those beliefs and practices had changed from the second to the fourth century, much less the 16th century.

The evolution of the word “catholic”

Collins recognizes this evolution, and he pegs a definition squarely in the pre-Nicene church: Here is his treatment of the word “catholic”:We recognize that the word “Catholic” is employed today by Roman Catholics and Protestants in much different ways than in previous centuries, and these differences reflect distinct theological traditions and ecclesiastical locations. In fact, the differing renderings of this common word epitomize a fair portion of our major argument throughout the book.

Since speaking out of our respective theological traditions might, given the disputed nature of the term, appear to be triumphalism or cause a gross misunderstanding, we suggest taking the principal meanings (historically and etymologically speaking) of the unabridged and highly reputable Oxford English Dictionary (OED) as a common ground and as an authoritative resource in this disputed area.

The OED points out that the word “Catholic” means “general” or “universal” or even “whole,” and it was expressed much earlier in Greek by the word καθολικός and in Latin by catholicus.

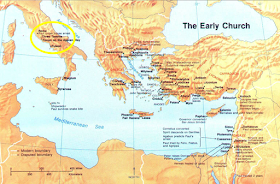

I’ve provided both a chart and a map nearby to show what is meant by “catholic” under this definition. The “catholic” church, in terms of the “one holy catholic and apostolic church”, when it was originally used, is reflected on the map nearby of the early third century church (borrowed from the “Eerdman’s Handbook to the History of Christianity” (1977). When the writers of the Niceno-Constantinopolitan Creed were thinking “catholic church”, you can see that the center of gravity of this “one holy catholic and apostolic church” was not located in Rome.

In addition to the map, the timeline shows the points in time of the various schisms in church history. There is a period of time, up to and after the adoption of the Niceno-Constantinopolitan creed (381) but prior to the Council of Ephesus (431), at which there was a professed doctrinal unity among the churches. This is what Collins calls “the ancient ecumenical church”, “when the Christian faithful were marked by considerable and broad unity”.

The Unity of the Ancient Ecumenical Church

The period of time up to “the great schisms” of the early fifth century (431 and 451) is the time referred to by the phrase “the ancient ecumenical church”. That phrase does have an etymology in works describing the eastern and Orthodox churches. I found it in the pithily-titled 1859 work, “Voices from the East. Documents on the present state and working of the Oriental Church, translated from the original Russ, Slavonic and French, with notes” – by John Mason Neale.Though Ignatius of Antioch, as a representative of the Eastern tradition and writing his letter to the Smyrnaeans in the early second century, was the first to employ the phrase “the Catholic Church” to describe the body of Christ (Rome once again was a latecomer here), nevertheless, given the subsequent history of the church, especially the schism that occurred between East and West in 1054, no one theological tradition can now accurately maintain that the “Catholic Church” subsists in its own particular communion of faith.

Indeed, to continue such usage fails to reckon with the basic facts of church history, troubling as they are at times, and it always results in the diminishment of other theological traditions, especially, in this case, Eastern Orthodoxy. Thus, in order to avoid this confusion, which entails considerable “wordplay” in which the part is repeatedly offered as the whole, we shall employ the phrase “the ancient ecumenical church” to refer to that early time up until the mid-fifth century, that is, the time of the Fourth Ecumenical Council at Chalcedon in 451, when the Christian faithful were marked by considerable and broad unity. We will therefore reserve the language of Roman Catholic to describe the discrete theological tradition that distinguished itself, especially from the East, and later emerged out of this prior unity, such as during the Third Synod at Toledo in 589, by departing from the earlier consensus of the ancient ecumenical church (see below).

Walls, Jerry L.; Collins, Kenneth J.. Roman but Not Catholic: What Remains at Stake 500 Years after the Reformation (pp. 22-23). Baker Publishing Group. Kindle Edition.

One final comment needs to be made. Earlier I’ve also cited Joseph Ratzinger (“God’s Word”).

By saying “Catholic”, it differentiates itself from a Christianity of Scripture alone and replaces this with the confession of the authority of the living word, that is, the office of apostolic succession. By saying “Roman”, it lends the office a firm direction, centered on the office of the keys of the successor of Peter in the city soaked with the blood of two apostles. Finally, by bringing the two terms together and saying “Roman Catholic”, it expresses that dialectic of primacy and episcopacy, comprehending a wealth of relationships, in which one cannot exist without the other.

A church that tries to be only “catholic”, without association with Rome, loses her very catholicity thereby. A church that—per impossibile—wanted only to be Roman, without being catholic, would similarly be denying herself and would reduce herself to a sect. The “Roman” guarantees true catholicity; the actual catholicity witnesses to the rights of Rome.

Thus at the same time, however, the formula expresses the twin breach that runs through the Church: first, the breach between “catholicism” and Christianity of the mere word of Scripture and, then, the breach between Christianity related to the Roman office of Peter, and Christianity that has separated itself from this (Ratzinger, Joseph Cardinal. God's Word (pp. 38-40). Ignatius Press. Kindle Edition).

The authors’ contention, then, in claiming that the Roman Catholic Church is “Roman but Not Catholic” is to point out that it has gone precisely in a direction that Herr Ratzinger warned against: “we affirm Roman Catholicism as a distinct Christian theological communion, though we recognize that some of the traditions and practices it has developed over the centuries may at times detract from both the power and the clarity of the gospel”.

In doing so, the Roman Catholic Church has, in spite of Ratzinger’s warnings, reduced itself to a sect.

I find it interesting/ironic that Roman Catholics take offense when Evangelicals use the term "Roman Catholic", but if the pope uses and defends that term, nobody bats an eye. Is this kind of like the situation where society is okay with African Americans using the N word, but nobody else is allowed to use it?

ReplyDeletehi Zipper -- it maybe seems that way. I think Ratzinger has more of a reasoned argument as to why "Roman" is necessary. But on the other hand, few day-to-day Catholics even care what the pope says.

Delete