Robert Price is an apostate, atheist, and mythicist, so I disagree with how he introduces this post, but what he says about secular humanism is instructive, as an insider to the movement:

http://www.robertmprice.mindvendor.com/zblog/?p=90290

Pages

▼

Saturday, January 07, 2017

Automatic writing

1. I'd like to consider two related objections to the historicity of Scripture.

i) Private conversations

In Biblical narratives we have many instances of what appear to be private conservations. A prima facie objection to the historicity of these conversations is that no witness was present, much less a stenographer, to take down what was said at the time. So how is the narrator privy to that information?

The "skeptical" explanation is that these are fictional conversations which the narrator put on the lips of the characters.

ii) Long speeches

Biblical narratives sometimes contain long speeches. The Sermon on the Mount is a case in point. How could the narrator or his source have verbatim recollection of a long speech he heard just once? People normally remember the gist of what was said.

2. Now let's consider some natural explanations:

i) Private conversations

In some cases, these may not be private conservations. When relaying a conversation, historians typically focus on the principals. That doesn't mean there weren't other people in attendance.

So in some cases, anonymous informants would be available. People in the entourage of the royal court, priestly establishment, and so forth, who are closet Christians, but keep their heads down to avoid having their heads unceremoniously separated from their bodies. Servants and courtiers who privately distain their employers, and are only to happy to leak unflattering information about their employers.

A more specific example might be the Beloved Disciple (John). He normally prefers to remain in the background rather than drawing attention to himself. He only comes forward at strategic points in the narrative to offer his eyewitness confirmation.

There are concentric social circles in the Fourth Gospel. You have an outermost circle of general followers. Then a smaller circle of the Twelve. Then an inner circle of Peter, James, and John. Then the inmost circle of Jesus and the Beloved Disciple. Apparently, John was Christ's most trusted confidant.

So even in scenes where only Jesus and someone else are mentioned, John may be a lurker. He generally maintains a low profile in the narrative to keep the focus on Jesus.

Regarding the Sermon on the Mount, I doubt Jesus said all that at one time. Jesus was an expert communicator, and that's just too much for an audience to absorb in one sitting.

Matthew has a habit of grouping related material. I think Jesus engaged in public teaching on that occasion, and Matthew used that as a hook to combine it with other things Jesus said on other occasions.

An advantage of writing is that you can reread the material. And it's easier to locate the material of it's grouped together by topic.

3. However, there are other cases where natural explanations don't seem to be as plausible. For instance, take conversations involving the patriarchs. There were no witnesses. No transcript which a later writer could consult. Perhaps, though, some of this might be passed down in family lore. Oral history.

Besides the Sermon on the Mount, another example is the farewell discourse, followed by the lengthy prayer of Jesus. That runs roughly from Jn 13:31 through the end of Jn 17. (Scholars disagree on where, exactly, it begins.)

That's a long, dense, dry speech (apart from the true vine parable). Not the kind of thing a listener could normally recall in detail from one hearing.

What about supernatural explanations? Christians can appeal to visionary revelation (which may include auditions), inspired memory, and verbal inspiration. And I think those are viable explanations. Now I'd like to briefly explore a neglected possibility.

According to some conventional definitions, automatic writing is writing produced without conscious intention as if of telepathic or spiritualistic origin, or writing produced by a spiritual, occult, or supernatural agency rather than by the conscious intention of the writer.

Assuming that the record of long speeches and private conversations can't be accounted for by natural means, suppose these are examples of automatic writing, inspired by the Holy Spirit? That wouldn't require the Bible writer to remember or know about the event.

4. Now let's consider some objections to that explanation:

i) It's special pleading. Why not just admit these are fictional speeches?

But is it special pleading? I didn't concoct a novel theory to defend the historicity of Scripture. Automatic writing is a well-documented phenomenon. I'm applying that preexistent phenomenon to these particular examples, as a possible explanation.

ii) Automatic writing is occultic!

It's true that automatic writing is associated with people who dabble in necromancy. However, just because there are ungodly examples of something mean there can't be godly examples of the same thing. The existence of false prophets doesn't taint true prophets. The existence of demonic miracles doesn't taint divine miracles. If lesser spirits can produce automatic writing, surely the Spirit of God is able to produce automatic writing. If evil spirits can produce automatic writing for evil purposes, surely the Holy Spirit can produce automatic writing for holy purposes.

iii) Automatic writing has a naturalistic explanation.

That objection conflicts with (ii). They can't both be right. At least, not across the board.

There's the question of whether "automatic writing" is loosely used to cover disparate phenomena. It's true that depth psychologists may say this is just a case of a human being naturally tapping into his subconscious. And, indeed, that may happen.

But automatic writing often takes place in the context of people who are striving to channel the dead. They endeavor to contact the dead. They open themselves to that influence. They wish to play host to that source.

So it's hardly a stretch to interpret the result as a case of possession by a supernatural agent. That interpretation lies on the face of the phenomenon.

(Which is not to deny that charlatans fake channeling the dead.)

iv) To invoke automatic writing is ad hoc. Where do you draw the line?

As with any explanation, you use it when it's necessary or reasonable to account for something that can't be as easily accounted for by some other explanation.

There are different modes of inspiration. The organic theory of inspiration will suffice for many examples of Scripture. But sometimes direct revelation is required. Sometimes visionary revelation is the source. By the same token, why not automatic writing in some instances?

Take visionary revelation. A seer will experience an altered state of consciousness. But that doesn't mean he always, or even usually, operates in that mindset. He couldn't function if he did. That's just when the Spirit comes upon him.

The Spirit can operate in more subtle and subliminal or more dramatic ways. It ranges along a continuum. At one end, an inspired writer may not be conscious of his inspiration. That's the organic theory of inspiration (e.g. Warfield).

At the other end, consider revelatory dreams and visions, where the Spirit takes possession of the human imagination. In that condition, the human agent is basically a passive recipient.

That would be analogous to the Spirit taking temporary control of a Bible writer to produce a text via automatic writing. That would be a type of verbal inspiration. Verbal inspiration in general doesn't require that. But it's a kind of verbal inspiration.

Friday, January 06, 2017

Scripture and scholarship

Recently, I was debating a Catholic who said Protestants claim "special access" to biblical truth through their historical and linguistic expertise. That echoes the Catholic meme that Protestants replace the papacy with a "priesthood of scholars". A catchy applause line, but is it true?

It's true that Protestants publish many commentaries on the Bible, but so do Catholics scholars, so if there's a "priesthood of scholars," that's common property of Catholicism and Protestantism alike.

But how accessible is the Bible without commentaries? How accessible is the Bible without background knowledge?

On the one hand, much of the Bible is comprehensible without any background knowledge. Historical narratives are generally accessible. Many Proverbs are transparent. Many statements in the NT letters are self-explanatory.

A philosopher with no background knowledge might have a better grasp of Romans (or parts of Romans) than a Bible scholar since much of the interpretation relies on grasping the flow of argument, which someone with an analytical mind and logical training as an advantage at tracing.

However, without background knowledge, a reader is prone to misinterpret some things. Likewise, there's much additional meaning he will miss.

Let's take a comparison. When Bram Stoker wrote his famous novel, it contained a fair amount of exposition because he was introducing a new kind of character to many readers.

However, that's become a genre. Many movies and TV dramas jump right into vampires because the audience is expected to understand the tropes of the genre.

But suppose someone who knows nothing about vampire lore watches some of this fare. At one level, he'll be able to understand much of what he sees. It will have a plot, dialogue, and characters that are fairly comprehensible.

But it will also contain tropes that are puzzling to someone who's unacquainted with vampire lore. Why the aversion to sunlight? Why the aversion to a crucifix or church sanctuary? Why can he be killed with a wooden stake through the heart, but he can't be killed by bullets? Why must a homeowner invite him into the house?

Why does he consume blood? Where did the fangs come from?

The viewer won't understand what motivates the character. If he's a science fiction buff, he might wonder if the character is an extraterrestrial, although that won't explain everything.

Discerning the Body

Along with Jn 6, 1 Cor 11:29 is a locus classicus for the Real Presence. For people conditioned by that theological tradition, it may seem self-evident to them that 1 Cor 11:29 is referring to the "true body" of Jesus. To deny that is to disregard the plain sense of the text.

But that interpretation overlooks two things: (i) the actual context, and (ii) Paul's use of "body" as a metaphor for the church. For instance:

Stratified treatment put the lie not only to the Greek ideal of friends' equality, but for Paul challenged the significance of the Lord's supper. Table fellowship was a binding covenant, and the one bread and body represented not only Jesus's sacrifice but those who partook together (10:16-17; cf. 12:12). This failure to discern the corporate body (11:29) led to sickness in their individual bodies (11:30; cf. the individual and corporate bodies as temples in 3:16-17; 6:19). C. Keener, 1-2 Corinthians (Cambridge, 2005), 96.

The reference to participating in the Lord's supper in an unworthy manner must be understood in light of the context, where the Corinthians were practicing the supper in a way that humiliated other members of Christ's body. To eat and drink in an unworthy manner is to eat and drink in a way that demeans, humiliates, or disrespects other members of Christ's community.

To examine oneself means to examine one's compliance with the covenant as reflected in their ways of relating to other members of the community and to discern the body of Christ must include recognizing that those other members of the community represent Christ himself (since they have been united with him) and must be treated as people for whom Christ chose to give up his life and to shed his blood. R. Ciampa & B. Rosner, The First Letter to the Corinthians (Eerdmans, 2010), 554-55.

But what does the "body" mean here? Were the reference to the body of Christ under the species of bread, one would expect a parallel reference to the blood of Christ under the species of wine, particularly since Paul twice emphasizes "eating" and "drinking." Paul, therefore, does not make the criterion an ability to distinguish the eucharist from an ordinary meal.

The only alternative, since "body" alone is mentioned, is to take "body" as meaning the community. If Paul's conventions of writing were the same as ours, he would have written "Body" in order to indicate that he had in mind the Body of Christ. He presumed that his readers would remember what he had written in his allusion to the eucharist in the previous chapter "We who are many are one body, for we all partake of one bread" (10:17).

Before celebrating the eucharist, Paul wanted the assembled Christians to examine themselves on their relationships with one another. Were they only members of the Body of Christ sharing a common existence? Did they really being to one another? Or were they merely in the same space as others, without any bond or exchange of energy? These questions should still be in the mind of every believer who participates in the service of reconciliation that precedes the liturgy of the eucharist in our churches. J. Murphy-O'Connor, 1 Corinthians (Doubleday, 1998), 123.

How “The Roman Catholic Church” “Compiled the Bible”?

I’m following up on some comments on the Jerry Walls Facebook thread, where he ridiculed the notion that the Roman Catholic Church claim to have “compiled the Bible” as “Simplistic, self-serving hubris”:

This paragraph of mine in the comments:

Got some comments of its own. One commenter wrote:

It is the very nature of this "early 'Catholic Church'" that is in question. Yes, they saw themselves as one church. But don't give people the notion that this group of Christians had uniform worship or organizational structures. In fact, that is the very thing that is in question.

1 Clement, written from Rome eastward (towards Corinth) reflects a different church government structure than does Ignatius (writing from the east westward). Easter was celebrated differently in the east (Quartodecimans) and in the west. They were by no means an organized body with an organized governmental or liturgical structures.

So who were "they", and by what mechanism did "they" "put it together"? Likely they had good communication among themselves, and a common purpose. But that can be said of the Southern Baptist Convention, and that in no way suggests organizational unity.

So who were "this group", and by what mechanism did "they" "put it together"? We have some evidence.

Paul wrote in the 50's and 60's. While they didn't have Kinko's there at the time, it's almost a sure bet that his letters were circulating as a unit as soon as Christians were able to regroup from persecutions. The Chester Beatty papyrus, dated 200, contains the complete set of Paul's letters.

The Gospels were written at different times and places. The Gospel of John is typically dated at around 90 AD. There is no question that these two sets of documents were compiled early and often. Stanley Porter says "there is surprisingly strong manuscript evidence worth considering that indicates that sometime in the second century the fixed corpus of four Gospels and Acts was firmly established" (How We Got the New Testament 87).

Tatian's Diatesseron, circa 150-180, is likely as early as they were all collected in one place. It is very likely that Irenaeus at least had all of these documents.

Porter also relates "Majescule Manuscript 0232", dated to the third century, which has compiled a Johanine corpus. No doubt these documents had been thought of as a unit and had been collected earlier (in order to create this compilation).

1 Peter, 2 Peter, and Jude were also compiled separately in an early codex.

Some date the Muratorian canon as early as 170; that contains virtually the whole NT canon.

This paragraph of mine in the comments:

Irenaeus may have had good theology, but that's because he also was among the first to have an almost totally compiled New Testament. It wasn't "the Catholic Church" that put it together. Paul's works were most likely collected in his own lifetime. The Gospels and other letters were also collected in a group -- but there was no doubt they were regarded as Scripture from the moment the ink was dry.

Got some comments of its own. One commenter wrote:

your last paragraph is utterly unsupported dogmatic affirmation--essentially a form of sanctified wishful thinking. … You're right that the NT was _mostly_ canonized in the second century, as far as we can tell. But clearly it _was_ the early "Catholic Church" (i.e., the group of Christians from whom all modern Christians are in one way or another descended) that put it together. Your claim that Paul's letters and the Gospels were compiled and accepted as Scripture almost as soon as they were written makes no sense if Irenaeus was the first person to be working with an "almost completed canon." That's 100 years later. I have trouble seeing how you aren't contradicting yourself here.

It is the very nature of this "early 'Catholic Church'" that is in question. Yes, they saw themselves as one church. But don't give people the notion that this group of Christians had uniform worship or organizational structures. In fact, that is the very thing that is in question.

1 Clement, written from Rome eastward (towards Corinth) reflects a different church government structure than does Ignatius (writing from the east westward). Easter was celebrated differently in the east (Quartodecimans) and in the west. They were by no means an organized body with an organized governmental or liturgical structures.

So who were "they", and by what mechanism did "they" "put it together"? Likely they had good communication among themselves, and a common purpose. But that can be said of the Southern Baptist Convention, and that in no way suggests organizational unity.

So who were "this group", and by what mechanism did "they" "put it together"? We have some evidence.

Paul wrote in the 50's and 60's. While they didn't have Kinko's there at the time, it's almost a sure bet that his letters were circulating as a unit as soon as Christians were able to regroup from persecutions. The Chester Beatty papyrus, dated 200, contains the complete set of Paul's letters.

The Gospels were written at different times and places. The Gospel of John is typically dated at around 90 AD. There is no question that these two sets of documents were compiled early and often. Stanley Porter says "there is surprisingly strong manuscript evidence worth considering that indicates that sometime in the second century the fixed corpus of four Gospels and Acts was firmly established" (How We Got the New Testament 87).

Tatian's Diatesseron, circa 150-180, is likely as early as they were all collected in one place. It is very likely that Irenaeus at least had all of these documents.

Porter also relates "Majescule Manuscript 0232", dated to the third century, which has compiled a Johanine corpus. No doubt these documents had been thought of as a unit and had been collected earlier (in order to create this compilation).

1 Peter, 2 Peter, and Jude were also compiled separately in an early codex.

Some date the Muratorian canon as early as 170; that contains virtually the whole NT canon.

The Deity

1. Let's begin with a crude formulation of the Trinity:

i) There is one God

ii) The Father is God

iii) The Son is God

iv) The Spirit is God

v) The Father is not the Son, &c.

On the face of it, this appears to be formally contradictory or polytheistic. Now a formal contradiction is just a verbal contradiction rather than a logical contradiction, so that, of itself, isn't all that concerning. If, however, we say that "God" has the same sense throughout, then it's much harder to eliminate a logical contradiction.

2. But suppose we don't define "God" in the same sense throughout. Suppose we introduce a distinction between "God" as an abstract noun and "God" as a concrete noun. As an abstract noun, "God" denotes divinity, divine nature. As a concrete noun, "God" denotes the particular being who is God (like an abstract particular). Let's plug that semantic distinction into a more refined formulation of the Trinity:

i) There is one God (concrete noun)

ii) The Father is God (abstract noun)

iii) The Son is God (abstract noun)

iv) The Spirit is God (abstract noun)

v) The Father is not the Son, &c.

Not only does that dissolve the formal contradiction, but there's no prima facie logical contradiction either. This is not to deny that the persons of the Trinity are individuals, but the semantic distinction concerns the definition of "God", and not their particularity as distinct individuals.

We could draw the same distinction using Latin synonyms. If we say there's one Deity, that's a concrete noun. If we refer to the deity of the Father, or Son, or Spirit, that's an abstract noun.

Now, I don't think a simple formulation of the Trinity can do it justice; I don't think individual words are adequate to capture the conceptual richness; but as simple formulations go, that's a good approximation.

Thursday, January 05, 2017

Intermission

i) I've discussed this before, but I'd like to approach it from a different angle. Both amils and premils (and postmils, I suppose) posit chronological gaps in some Bible prophecies. That can look like special pleading. A face-saving device to savage your eschatological timetable. Or, more seriously, a face-saving device to salvage the prophecy itself.

Now, I do think Christians of whatever eschatological outlook (amil premil, postmil) can be at risk of postulating ad hoc gaps to protect their position. And I'm not sure we can entirely guard against that. We need to make allowance for the possibility that our prophetic school of thought is mistaken. (That's different from saying the prophecy itself is mistaken.) And we need to have general evidence for our eschatological outlook. We can't be constantly patching it up.

ii) On a related note, some people are suspicious or dubious about Bible prophecy because they've seen how millennial cults devise creative interpretations when their founding prophet makes false predictions. And they think Christian apologists are guilty of the same antics when defending the Bible.

iii) And I think skepticism is often justified in assessing prophetic claimants. As even Scripture says, "many false prophets have gone out into the world" (1 Jn 4:1). The Bible warns of false prophets.

iv) That said, I'd like to make a preliminary point. If there's evidence outside of Scripture that some people can sense the future (e.g. premonitions, premonitory dreams), then that establishes both the possibility and reality of genuine prophetic foresight. And it doesn't take many examples to establish the existence or occurrence of a particular phenomenon. If you have that baseline, then it should affect the presumption you bring to Scripture. At the very least, that ought to make you more sympathetic.

v) The next point I'd like to explore is whether the notion of prophetic gaps is inherently suspect. Let's consider the idea of Bible prophecy. Even if you don't initially believe it, ask yourself what it would be like in case it's for real. What would a seer experience?

We need to remind ourselves that Bible prophecy is typically a two-stage process. That's easy forget because all we have is the record of vision. So that makes it look like a one-stage process. Since we're reading a prophecy, our default mode is to judge it on those terms. But that's misleading. A visionary revelation didn't originate in writing.

Let's begin with our ordinary waking perception of temporal succession. We experience the "passage of time" continuously. Instant by instant.

I can't jump ahead from 1:00 to 2:00. I can't skip over the intervening time. Rather, I must live through each moment to get from 1:00 to 2:00. Unless I suffer a blackout, there are no chronological gaps in my experience of real time.

Compare that to visionary revelation. Imagine what it's like to be a seer. Suppose, one night, you experience a series of prophetic dreams. It's like watching a movie in your head. You see one scene after another. The scenes keep changing. Then you wake up and write them down.

Now, writing is a different medium than seeing. There are no gaps on the printed page. When you write down what you saw, you don't insert blank spaces between one section and another. Rather, you just write down what you saw in the order in which you remember having seen it–in tidy, evenly spaced paragraphs.

So when we read a prophecy, the written record is continuous. There are no breaks on the page.

Yet that's just an artifact of how to represent an experience in writing. It's a category mistake to confuse the nature of the underlying experience with the nature of a textual description.

Let's go back to the experience of visionary revelation. Suppose these are visions of the future. A series of visions. But here's the thing: there's nothing in what he sees that shows him how much time passes between one scene and another. Serial visionary revelation is discontinuous. A vision of disconnected scenes.

So there's nothing in the visionary experience to indicate the actual duration of the intervals between one future scene and another. There's an implicit gap between each scene and the next scene. Abrupt scene changes.

There's no indication that the envisioned events occur in rapid succession, or evenly spaced intervals. If you think about it, it would be rather disorienting to witness. The seer's imagination is bombarded with shifting, disjointed scenes. He saw this, that, and the other thing.

So the fulfillment of these visions could well be staggered. That's not a case of wedging gaps between a continuum. To the contrary, there's already "space" between one scene and another. And there's no telling how much space separates one scene from another. It could be a brief interlude or centuries apart.

Consider movies where the action cuts ahead to ten years later. Say you were watching a scene of teenage boyfriend and girlfriend. A moment later, you see a scene of the teenagers all grown up. Married with kids. The director expects the audience to make the mental transition.

So there's nothing intrinsically suspect about the notion that Bible prophecies contain chronological gaps. Indeed, if you think it about it, that's to be expected. And there'd be no interruptions in the text (hence, no textual clues) since the mechanics of recording the experience are fundamentally different from the mechanics of the recorded experience.

The interesting question isn't whether there may be the occasional prophetic gap, but whether a reader is even aware of where they lie, in which case prophecy might be riddled with gaps.

Debunking an over-used Irenaeus quote on “Papal Succession”

|

| In this definitive work on Irenaeus the city of Rome is not even mentioned. |

The great early Father, St. Irenaeus in the mid-100’s felt a little differently (Against Heresies III, 2-4):

[T]hat tradition derived from the apostles, of the very great, the very ancient, and universally known Church founded and organized at Rome by the two most glorious apostles, Peter and Paul; as also [by pointing out] the faith preached to men, which comes down to our time by means of the successions of the bishops. For it is a matter of necessity that every Church should agree with this Church, on account of its preeminent authority, that is, the faithful everywhere, inasmuch as the tradition has been preserved continuously by those [faithful men] who exist everywhere.

The blessed apostles, then, having founded and built up the Church, committed into the hands of Linus the office of the episcopate. Of this Linus, Paul makes mention in the Epistles to Timothy. To him succeeded Anacletus; and after him, in the third place from the apostles, Clement was allotted the bishopric. This man, as he had seen the blessed apostles, and had been conversant with them, might be said to have the preaching of the apostles still echoing [in his ears], and their traditions before his eyes. Nor was he alone [in this], for there were many still remaining who had received instructions from the apostles....

Soter having succeeded Anicetus, Eleutherius does now, in the twelfth place from the apostles, hold the inheritance of the episcopate. In this order, and by this succession, the ecclesiastical tradition from the apostles, and the preaching of the truth, have come down to us. And this is most abundant proof that there is one and the same vivifying faith, which has been preserved in the Church from the apostles until now, and handed down in truth.”

Jerry referred them to Peter Lampe; someone else commented that “if you don’t have a succinct answer, you probably don’t have an answer”. Here is a succinct response that I posted:

Wednesday, January 04, 2017

Tuesday, January 03, 2017

Light through the keyhole

At its best, atheist experience is like a man locked away in a pitch black room, daydreaming of summer. Subjective hope.

At its worst, Christian experience is like a man locked away in a windowless, unlit room with a sliver of light shining through the keyhole from the summery world beyond. Objective hope.

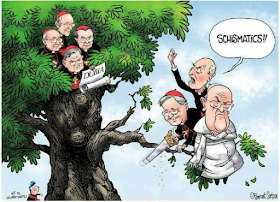

“Pope Francis” is in the minority. But the winds of change are blowing.

|

| Bishops and Cardinals vs Pope Francis. But the progressives are with him. |

The Four Cardinals Are Up 14-9. But Leonardo Boff Is in the Game, Too.

It seems likely to me that “Pope Francis” will go to his grave not having responded to the dubia, the yes-or-no “questions” which essentially ask “Pope Francis”, “does your teaching supersede that of “Pope John Paul” on the issue?” (“Pope John Paul II” seemingly unequivocally ruled out what “Pope Francis” now has opened the door to in the name of “mercy”):

The past six months have seemed at times like a war of attrition. The controversy has centred largely on how the Pope’s words are to be interpreted. Some national bishops’ conferences – Germany, for example – seem more or less united in favour of liberalising the discipline, while others – such as Poland – insist that nothing has changed. The bishops of Buenos Aires produced a document suggesting that the way is now open for Communion for the remarried in some cases where subjective guilt might be diminished. The Pope responded with a private letter commending this interpretation as the right one. In what has become a familiar aspect of disputes around the Pope’s real intentions, the purportedly private exchange was leaked – a transparent attempt to give momentum to the liberalising tendency.

Christology and compound words

Lee Irons is leading the charge for the eternal generation of the Son based on the traditional rendering of monogenes (μονογενής) as "only-begotten". Lee is a fine scholar, so he's a good spokesman for that position.

The word occurs in Jn 1:14,18; 3:16,18 & 1 Jn 4:9. And that understanding was codified in the Nicene Creed.

I've already explained my own position. I affirm eternal Sonship but deny eternal generation:

But now I'd like to raise a linguistic issue. Monogenes is a compound word. Sometimes the meaning of a compound word is a combination of what the constituent words individually mean. And that's the unquestioned assumption or inference when monogenes is rendered "only-begotten". Proponents of eternal generation justify their position on the supposition that monogenes has the conjoined meaning of the two individual words that compose it.

Put another way, they presume the compound word has a transparent meaning, by combining what each of the two words mean. And certainly the import of many compound words follows that simple additive principle. To take a few English examples: bedtime, dishwasher, football, footpath, headache, headlight, northwest, rowboat, shortsighted, taillight, teapot, toothbrush.

In cases like that, if you know the meaning of the uncompounded words, you can figure out the meaning of the compound word.

But many times, a compound word has an idiomatic meaning that's not derivable from the conjoined import of the uncompounded words that compose it. To take a few English examples: acidhead, callgirl, cottonmouth, cyberspace, dot.com, flying saucer, grease monkey, greenhouse, homesick, hotdog, jailbird, kickback, ladybug, soap opera.

(In English, a compound word can be solid, hyphenated, or open.)

You can't tell what these words mean by simply combining the individual import of each word.

To take an analogous example, compare these two sentences:

Luigi is waiting for the coin to drop

Let's drop the dime on Luigi

To someone who doesn't know English well, these seem to be semantically equivalent phrases, but of course, they are completely different.

Given that compound words can have, and often do have, idiomatic meanings (and I believe that holds true for Greek as well as English), are proponents of eternal generation justified in simply assuming that monogenes has a transparent meaning–or is that unwarranted unless they present an argument to exclude the real possibility that it's idiomatic?

Monday, January 02, 2017

Are the Resurrection accounts irreconcilable?

i) Critics often say the Resurrection accounts are contradictory. Even if that were true, it wouldn't mean the Resurrection is in doubt. You can have discrepant accounts of a plane crash, but that doesn't mean there was no plane crash. The fact that eyewitnesses may get details wrong doesn't mean they mistook the underlying event.

ii) There is, however, a basic confusion about the oft-repeated claim that the Resurrection accounts are irreconcilable. It's possible for the Resurrection accounts to be irreconcilable, yet each account is completely accurate. It doesn't take much imagination to see how that's possible, but critics lack imagination.

iii) Let's begin by considering how to represent the same scene in time and space. Suppose I photograph a landscape. Say I photographic the same scene from two different angles. I now have two different pictures of the same scene.

Suppose I turn these two pictures into two different puzzles. Two boxes of puzzle pieces depicting that scene.

Even though these are both depictions of the same scene, no piece from one puzzle will fit into any piece from the other puzzle. The pieces from these two puzzles are irreconcilable.

I can't map one puzzle onto the other puzzle, yet both puzzles map onto the same underlying scene. Two completely accurate, but irreconcilable depictions.

iv) Or, instead of shots from different angles, I could take two shots at different times. I might photograph the same scene morning and afternoon, Or spring, summer, fall, and winter.

I'd shoot the same scene at the same angle, but each picture would look different due to different lighting conditions, weather, deciduous trees in bud, or turning brown, &c.

Once again, I could turn these pictures into puzzles. But I couldn't piece the scene together using pieces from different puzzle boxes. Yet each separate depiction is a completely accurate representation of the same scene.

v) In addition, when we assemble a puzzle, we have the benefit of the complete picture on the cover to use as a guide. That gives us the part/whole relation.

But in the case of the Resurrection accounts, we don't have direct access to the original scene. All we have to go by are edited accounts. We're comparing each account with another account, rather than comparing each account to the original. It's like piecing a puzzle together after the picture on the box top was lost. All you have are pieces. You don't have an image that shows the original composition.

vi) In addition, the Resurrection accounts are very selective. So that's like attempting to assemble a puzzle with missing pieces.

But even if you can't reconstruct the original scene, that creates no presumption against the accuracy of the accounts. Just as your inability to assemble a puzzle using pieces from different puzzles (of the same scene, from different angles or seasons) doesn't mean the representation is inaccurate. Just as your inability to assemble a puzzle with missing pieces or a missing box top picture doesn't mean the representation is inaccurate.

vii) Incidentally, the same group of people could go to a park or cemetery at the same time, but miss connections because various objects obstruct their view of each other. Even if they were all there at the same time, they may not see each other, depending where they stand in relation to trees, buildings, hillocks, &c.

viii) Dropping the metaphor, let's take a comparison. We have parallel accounts of Jesus cursing the fig tree in Matthew and Mark. These are clearly about the same event. It's likely that Mark preserves the original order. In Mark, Jesus curses the fig tree as he enters Jerusalem, then cleanses the temple, then exits Jerusalem by the same route. Next day, the disciples see the withered tree. In-between coming and going, there's the cleansing of the temple.

By contrast, Matthew exhibits narrative compression. Matthew places the cleaning of the temple before the cursing of the fig tree. That reduces a three-stage action, spread over two days, to a two stage action.

That's a useful example of how a Gospel writer (Matthew) edits a source. And if Matthew was all we had to go by, we'd be unable to reconstruct the original sequence, both because we're missing key information, and because historical events, due to their contingency, often have no necessary sequence. We don't not know in advance when somebody will do something in relation to something else. He might curse the fig tree first, then cleanse the temple–or cleanse the temple first, then curse the fig tree. The order of events is up to the discretion of the agent, which makes it unpredictable. What was sooner? What was later?

Unless we were there and saw what happened, it's often impossible to say who did what when. For there's more than one way it might have happened. Given different possibilities, we can't expect to nail down the chronology in many cases.

Consider all the things you do in the course of a day. In some instances, you have to do one thing before you can do something else. But in many instances, there's no fixed order in which you must do them. And those may be snap decisions you make on the spot.

Sunday, January 01, 2017

Religion of life, religion of death

One way to classify religions is by how they address the question of death and the afterlife. Indeed, it's sometimes said, with tolerable exaggeration, that death is why religion exists in the first place.

Hinduism espouses reincarnation. I think the notion of reincarnation is one of the few things that's as bad as atheism. The notion that you're condemned to repeatedly start a new life all over again, with a new set of parents, grandparents, aunts, uncles, cousins, brothers, sisters, childhood friends, adult friends, spouse, sons, daughters, &c, only to lose everything time and again, is truly hellish.

Buddhism inherits reincarnation from Hinduism. Buddhism is all about transience, so reincarnation doesn't really belong in Buddhism.

Many pagan religions practice some form of ancestor worship, like necromancy.

From what I've read, the concept of Vahalla was an extension of how Viking heroes lived. In addition, I could cite Greco-Roman and ancient Near-Eastern examples. But that will suffice. None of this is very inviting, even if it were true.

Now I'd like to contrast Christianity and Judaism. In this context, what I mean by Judaism isn't OT Judaism or Christian Judaism but post-Christian Judaism. Medieval and modern Judaism.

I'll begin with an overstatement, then scale it back by qualification. Judaism is a religion of life while Christianity is a religion of death. Of course, that's hyperbolic, but the contrast is truer for Judaism than Christianity.

In my observation, Jews stress how to lead a good life. A full, honorable, virtuous life. Make the most of life. Family and friends. Civil duties. Emphasis on social ethics.

Obviously, that overlaps with Christianity. We care about that, too.

Moreover, Protestants rediscovered family life as a godly vocation. A setting in which to be happy and holy.

Still, each of us is tending towards the grave. Recently I skimmed a book by a rabbi. As a young rabbi he was ill-equipped for the task, because men of the cloth are expected to visit dying parishioners in the hospital, yet his rabbinical training didn't give him anything helpful to say to the dying–or to the living who were about to lose a loved one, or to the bereaved.

I'm not saying modern-day Jews don't believe in the afterlife. Some do, some don't. But from what I can tell, Judaism has a this-worldly center of gravity.

Yet that's a serious deficiency, for what ultimately matters is not how the story begins, but how it ends. Given a choice, it's better to start off badly but end well than to start off well but end badly. The ending is for keeps.

The end of life is the acid test of religion. That's when the promises come due. When the promises must come true. That's when it has to be real. That's when it counts.

We pray. We preach. We define the faith. We defend the faith.

But the deathbed is where our hopes must be redeemed, as this life fades, and we face eternity.

Some of our forebears were otherworldly to a fault. But to be fair, life for many Christians used to be wretched. Famine. High infant morality. Painful, incurable, untreatable diseases. Many widows, widowers, and orphans. Death was always near. Hunger was always near. Cramp cold quarters.

If contemporary Christians in the west are less otherworldly than their forbears, that's in large part because life is generally so much more enjoyable than it use to be, thanks to technology, as well as greater political and economic freedom. And we ought to be grateful for natural goods.

Yet, a religion of life is only useful to the living. What we all ultimately need, more than a religion of life, is a religion of death.

For life is short. Even at its best, life is full of heartache and heartbreak. And the better your life, the more you have to lose. The world is not enough.

Q. What is your only comfort in life and in death?

A. That I am not my own, but belong—body and soul, in life and in death—to my faithful Savior, Jesus Christ.

A. That I am not my own, but belong—body and soul, in life and in death—to my faithful Savior, Jesus Christ.

He has fully paid for all my sins with his precious blood, and has set me free from the tyranny of the devil. He also watches over me in such a way that not a hair can fall from my head without the will of my Father in heaven; in fact, all things must work together for my salvation.

Because I belong to him, Christ, by his Holy Spirit, assures me of eternal life and makes me wholeheartedly willing and ready from now on to live for him.

Journey to nowhere

A few more comments on this:

Doubt, lack of certainty, skepticism. Call it what you will. The experience is inevitable in the Christian faith.We all get to points in our lives where we just don’t “know what we believe anymore.”

You have to wonder if Enns believes his own propaganda. Does he really believe these hasty generalizations? Is he so insular that he truly believes every Christian, or even most Christians, "inevitably" get to points in life they just don't know what they believe anymore? Sure, that's true for some professing believers. But it's hardly inevitable. It's hardly true for every professing believer.

When we enter that period, our first priority is not to get out of it, fix it, and bring it all back to the way it was.Once the doubt hits, there is no going back to the way things were.

Another hasty generalization. Again, is he really so insular to think that's the case? Certainly there are people who never get back to the way things were. But certainly there are people who do recover.

Our only choice is how to live, and for people of faith I see three choices:1. Make believe nothing happened and everything is OK. Stay in the game, bury your thoughts, and keep on as usual.2. Think of that period as a temporary bump in the road, and if handled properly, you will safely wind up back where you were, perhaps with even greater resolve.In Evangelical and Fundamentalist circles, choices 1 and 2 reign: “Stop making waves and get with the program” or “My period of doubt was simply a momentary lack of faith on my part, but now I have clearer reasons for why my faith is just fine as it is.”

Notice his scornful attitude towards (1) and (2). And, once again, is he so insular that he doesn't know any better? There are, in fact, Christians who suffer a crisis of faith, but work through it and come out the other end with their original beliefs intact, and they are stronger as a result of that crisis. They now have a battle-hardened faith. They now have clearer reasons for what they believed.

The trick, as many skeptical Christians have found out the hard way, is finding people to talk with about their doubts without being made to feel like they just “don’t get it.” As a college professor I deal with these types of inner struggles in my students on a regular basis.

Of course, schools like Eastern College, where Peter Enns and Kent Sparks teach, aggressively subvert the faith of students. Their "inner struggles" are the direct result of what they hear in the classroom.

Enns isn't a reluctant "sceptic". Enns is proud of the fact that he no longer believes what he used to believe. He derives self-esteem from belonging to the smart set.

3. Accept that period as an opportunity for spiritual growth, an invitation to take a pilgrimage of faith without predetermined results.For me, choice 3 is far more intellectually appealing and spiritually satisfying:“I’m not sure what has happened and I’d give anything to go back to the way things were. But I know that can’t be. Instead I choose to try and trust God even in this process, to see where the Spirit will lead, even if I don’t know where that is. I need to let go of thoughts and “positions” that gave me (false) confidence and begin the journey toward learning to rely on God rather than ‘my faith.’”

The obvious problem with that euphemistic description is that it's vicious circular. Given his skepticism, he has no justification for believing there is a God at the end of the journey. No justification for believing that God is leading him on a pilgrimage of faith.

For all his self-congratulatory rationalism, Enns is a shallow, incoherent thinker. Although Enns constantly indulges in intellectual posturing, his bromides are logical nonsense. He's like the swami or Tibetan monk in B-movies who dishes out pseudoprofound twaddle.