Pages

▼

Saturday, February 13, 2016

How To Damage Trump

Something I just posted in a thread at National Review:

Here are a few of the points I'd like to see made against Trump in tonight's debate (and others):

- No other Republican candidate has as close a relationship with the Clintons as Trump does. The Clinton campaign would be able to run ads featuring Trump's previous endorsements of Clinton. There's general agreement among Republicans, including Trump's supporters and self-identified liberals and moderates, that we want to defeat Clinton. Trump's lengthy and explicit record of supporting the Clintons would make him uniquely weak as a Republican nominee.

- Nobody has worse general election numbers than Trump. Rubio would be the best one to highlight this point, since his numbers are among the best. (Carson has some good numbers as well, sometimes even better than Rubio's, but he's not as good of a communicator and has shown so little interest in going after Trump, so Rubio would be better at bringing up this issue.)

- Trump is remarkably self-contradictory. Cruz could use Trump's flip-flops on whether Cruz is eligible for the presidency as an example, then cite other examples. I'd suggest making the criticism as forceful as possible, such as by saying that Trump is the most self-contradictory candidate to ever run for the presidency. In addition to "self-contradictory", I'd use the term "unstable". That has broader implications, and it's an accurate description of Trump.

- Mention at least twice (to make sure it gets remembered) that Trump openly boasts about committing adultery with many women. That's another way in which Trump is uniquely corrupt. As bad as Bill Clinton is, at least he didn't brag about his adulteries in a book he published. Bringing up this aspect of Trump's character should be especially helpful in states with large religious populations, like South Carolina and other states coming up soon. People want to like the president at a personal level, probably more so than with any other office in our nation. Trust is important. How much will people trust somebody who publishes a book bragging about damaging so many lives through adultery? (I'd recommend that the people criticizing Trump even refer to how he "destroyed homes", "wrecked lives", "ruined marriages", etc.)

Friday, February 12, 2016

Adam and Eve: An Evangelical Impasse?

Scroll down to p165:

Hans Madueme, Adam and Eve: An Evangelical Impasse?

The Pope and the Patriarch

|

| The

main point of discussion was, “how far have fashions in clerical garb diverged in 1000 years?” |

The Russian Orthodox church is the largest now among a number of “autocephalous”, or “independent” Orthodox bodies, which are descended from the eastern churches when Rome split with them in 1054 AD. Today, the individual “Orthodox” church bodies in each country, while professing the same “faith”, and claiming the same “apostolic succession” of bishops, are functionally and governmentally independent from one another.

|

After the meeting, “Pope Francis”

proposed replacing the papal

skullcap with

a Mexican Sombrero for all state meetings.

|

One major point of discussion was how far fashion in clerical vestments had diverged since the eleventh century. After the meeting, exhibiting how “development of doctrine” works in real life, “Pope Francis”, exhibiting a bit of headgear-envy, proposed that the papal skullcap be replaced at State meetings with the Mexican Sombrero.

Inspiration, evidentialism, and harmonization

1. Lydia McGrew posted a critique of how Michael Licona approaches the issue of Gospel harmonization. I posted a response. She commented on my response.

It challenging to find an entry point into this discussion, because it's so complicated. There's the specific question of Michael Licona's position.

Then there's the question of how inerrantist Bible scholars harmonize the Gospels. I have in mind representative scholars like Poythress, Stein, Block, and Blomberg–although Blomberg is less reliable than he used to be. Of late he's been exploring loopholes.

2. Then there's Lydia's own position regarding what's a permissible or impermissible harmonization. That's illustrated by stock examples, viz. was Jesus crucified on Passover?, the anointing of Jesus, the temple cleansing, the centurion's servant, cursing the fig tree, raising Jairus's daughter.

I have a problem with her set-up. She draws a number of significant conceptual distinctions. She deploys her distinctions to say there's a crucial difference between Matthew doing X with Mark and Matthew doing Y with Mark. X is acceptable but Y is not. Same thing with John doing something to Mark, or Luke doing something to Mark.

But that's too abstract and premature. It attempts to predetermine what they could or couldn't do before we even crack open the pages of Scripture to see what in fact they did. That's the wrong starting-point.

For me, we need to begin by looking at what they actually did. What's the most plausible interpretation?

3. Lydia uses evidentialism as a frame of reference, in contrast to Licona's position. That's an old debate, and there are different ways to block this out.

i) Historically, Aquinas represents a tradition in which you stress the role of proof. Certain beliefs are demonstrable. Knowledge or scientia is grounded in what you can prove.

But for Aquinas, that high standard already begins to break down at the very point where you'd like it to hold. Although the truths of natural revelation are said to be demonstrable, the "mysteries of faith" are strictly indemonstrable.

ii) Writers like Thomas Reid, Bishop Butler, and John Locke represent a different tradition, a different paradigm. They lower the bar. For them, it's not about proving Christianity, but the rationality of Christian faith. Providing reasonable grounds for faith, rather than demonstrative arguments. To recast this in modern terms, what kind of evidence is necessary for justified or warranted belief.

iii) Writers like Calvin and Owen represent yet another tradition or paradigm. For them, it's not primarily about criteria or corroborative evidence, but self-authenticating Scripture and the witness of the Spirit.

4. Another way to block this out is to evoke Chisolm's distinction between methodism and particularism. I think Lydia's evidentialism is clearly in the methodist corner. On this view, you begin with criteria, which you use to sort out true religious claimants from false religious claimants. In one respect, this is a top-down approach. It begins with criteria rather than phenomena or experience.

By contrast, the approach of Calvin, Owen et al. represents particularism, by taking paradigm-cases (Scripture) and paradigm examples of religious experience (the witness of the Spirit) as the starting-point. That's a bottom-up approach in the sense that it begins with particular instances rather than general criteria. But in a different respect, it's a top-down approach by treating the Bible as the criterion. On this view, inspiration is a presupposition rather than a conclusion.

5. This goes to another distinction. Evidentialism tends to treat the Bible as a source of information about supernatural events, whereas writers like Calvin and Owen regard the Bible as a supernatural event in its own right. Are the Scriptures a supernatural product?

6. Let's begin with a crude version of evidentialism. Initially, we should approach the NT documents as primary source materials. Historical sources.

At this stage of the argument, we don't treat them as inspired sources. Rather, we assess them like we'd assess any ostensible historical testimony.

Using criteria which historians typically use, we judge the NT documents, or a subset thereof (e.g. Gospels, Acts, 1 Corinthians), to be generally reliable.

On that basis, we conclude that the Resurrection probably happened. If so, that has far-reaching implications. To some degree, that circles back around to retroactively validate other core historical events in the life of Christ.

One objection to this approach is that reported miracles greatly lower the likelihood that the account is true. By definition, miracles are highly improbable events.

The McGrews are aware of this objection. So they supplement evidentialism with a case for miracles.

In addition, although a miracle presumes the existence of God, it doesn't presume belief in God. It isn't necessary to prove God's existence before you can credit the occurrence of a miracle.

Lydia can correct me if that's inaccurate.

7. How should we assess these competing paradigms? Are they contradictory or complementary?

Apologetics, especially offensive apologetics, is undeniably methodist. It uses criteria and rules of evidence to broker religious claims and historical claims. To be persuasive, to avoid begging the question, it seeks common ground in methods and assumptions which Christians and reasonable unbelievers share in common.

This also has some value in defensive apologetics. Believers can benefit from having evidence they can point to, and reasons they can give.

8. However, evidentialism has weaknesses:

i) There's a circular relationship between your criteria and your worldview. What you think is possible or probable is contingent on the kind of world you think we inhabit. Whether a rule of evideence is reasonable or unreasonable is contingent on what you think reality is like. They need to match up.

ii) Most Christians, at most times and places, lack the intellectual aptitude or access to corroborative evidence to make a philosophically solid case for what they believe. But if, in fact, Christianity is true, that means the truth of Christianity must be accessible at a different level.

This doesn't necessarily mean reason and evidence are dispensable. It might still be important say that, at least in principle, the Christian faith is rationally defensible. Moreover, that some Christians have risen to the challenge.

iii) Another problem is that I don't see where inspiration figures in Lydia's position. If the Bible is inerrant (or infallible), that's the result of plenary, verbal inspiration. If the Bible is fallible, that's because it's uninspired, or intermittently inspired.

I don't see where inspiration has a role to play in evidentialism. Where does it come into the argument? Where does it ever merge with the traffic? I don't see a logical place for inspiration to break into the flow of argument.

9. What about the alternative?

i) On the face of it, it might seem like the position of Calvin, Owen et al. is specially pleading. An ad hoc position to preempt appeal to ecclesiastical authority.

Another complication is the relationship between self-authenticating Scripture and the witness of the Spirit. Are these two different principles? How do they interact?

ii) I don't Calvin's appeal is just a makeshift apologetic maneuver. He describes self-authenticating Scripture and the witness of the Spirit in very autobiographical terms, as if that's how he did, in fact, experience Scripture.

iii) We should treat things the way they are. If the Bible is the word of God, then that's how it ought to be treated. It should not be treated as something it is not. Something less or lesser than what it truly is.

iv) I'd say there are affinities between Calvin's epistemology and Newman's illative sense and Polanyi's tacit knowledge. It's not an idiosyncratic position, but reflects a model of knowledge that's more subliminal.

Take voice recognition. For most of us, that's intuitive. We simply recognize the person on the other end of the receiver. It's not something we could prove.

On the other hand, that's not purely subjective. Every voice has a distinctive timbre. That's subject to scientific analysis.

On this view, regeneration restores our native ability to perceive religious truth. It doesn't add new evidence, or add a new faculty. Rather, the repairs a natural faculty.

10. But even if the Bible is self-authenticating, where do we break into that charmed circle? After all, there are rival revelatory claimants.

i) It depends. If you experience the Bible in a certain way, then it's direct. An immediate, veridical experience.

Moreover, this isn't just subjective, for many Christians have the same experience. So you have that intersubjectival confirmation.

Even sensory perception has an ineluctably private dimension. I don't know what's going on in your mind when you see a tree. I can't tap into your experience. I can't tap into your mental state.

We can compare notes. You can tell me what you perceive, and I can tell you what I perceive. Same thing with intellectual apprehension.

ii) However, this doesn't preclude appeal to external evidence. These are not in tension. It can be complemented by theistic proofs, the argument from prophecy, the argument from miracles, answered prayer, historical evidence, &c.

Thursday, February 11, 2016

Jesus and Romulus

Richard Carrier published a book in which he argues that Jesus never existed. I was reading a review:

The reviewer picks out key items in Carrier's case for mythicism. I'm going to comment on those items.

Carrier does ask good questions. Why do so many first century extrabiblical sources fail to mention Jesus or Christianity, if Jesus existed in the first century?

i) Jesus was a local celebrity. He wasn't widely known. This wasn't the television era. He was well-known in pockets of Palestine, but completely unknown in most of the Roman Empire. Most folks in the Roman Empire would have no occasion to be aware of a short-lived Palestinian celebrity. It would take time for that information to disseminate.

ii) Our sources of information for that time and place are sparse and spotty.

Why does Paul so often fail to mention aspects of Jesus’ life and teaching?

That's an old canard:

i) There's the difference in genre. Paul is a letter-writer, not a biographer.

ii) Paul had less direct knowledge of Jesus than people who accompanied Jesus during his public ministry.

iii) Since Luke was Paul's friend and traveling companion, assuming Paul had firsthand and/or secondhand knowledge of Jesus, he probably shared that with Luke. Paul needn't write a separate account concerning the life of Christ if what he knew fed into Luke's Gospel. In that event, Luke's Gospel includes whatever Paul had to contribute.

iv) That isn't pure speculation. For instance, Luke's account of the Last Supper is more like Paul's account in 1 Corinthians than Matthew or Mark. So there may well be cross-pollination between Luke's knowledge of the historical Jesus and Paul's, or vice versa.

Why did Epiphanius (Panarion 29.3) and rabbinic sources (Carrier cites BT Sanhedrin 107b; Sotah 47a; JT Hagigah 2.2; Sanhedrin 23c) mention a view that Jesus lived during the time of Alexander Jannaeus, which was a century before the historical Jesus supposedly lived? For Carrier, this is an indication that early Christians differed on where to put Jesus in history, which would be odd, had Jesus been historical.

i) For Carrier to cite the Talmud is a double-edged sword. After all, the Talmud bears witness to Jesus, albeit with a polemical slant:

Jesus was hanged on Passover Eve. Forty days previously the herald had cried, “He is being led out for stoning, because he has practiced sorcery and led Israel astray and enticed them into apostasy. Whosoever has anything to say in his defense, let him come and declare it.” As nothing was brought forward in his defense, he was hanged on Passover Eve.Tractate Sanhedrin (43a).

This bears witness, not only to Jesus' existence, but his reputation as a miracle-worker. And it's more impressive because it represents a hostile witness.

ii) In addition, there's evidence that the Talmud was censored to suppress historical references to Jesus:

iii) The Talmud is a mishmash of legend and historical traditions. It isn't easy sift the material.

iv) If, moreover, Jesus never existed, then why didn't Jews capitalize on that damning fact? Why wasn't that a fixture of the Jewish polemic against Christianity? Surely Jews were in a uniquely qualified position to challenge the existence of Jesus–if, in fact, he was purely a figure of myth and legend.

v) It's easy to overlook the fact that many people know very little about the past, have a very shaky grasp of relative chronology. Let's take two examples, beginning with the Pilgrimage of Etheria, about a 4C nun who made a trek to the Holy Land. It's clear from her account that she has, at best only the sketchiest grasp of how to correlate Biblical events and place-names to locations in the Holy Land. She's entirely dependent on local traditions and ecclesiastical traditions.

To take another example: Cotten Mather's commentary on Genesis (Biblia Americana: Genesis). Mather is often completely at sea regarding historical identifications, regarding when and where people lived and events occurred, in the text of Genesis.

For all its limitations, archeology has given us a far more accurate relative chronology of ancient history. More so than many ancient people enjoyed.

vi) As one scholar notes:

The garbled, muddled nature of the Babylonian version [i.e. Babylonian Talmud] is evident in the strange story of Ben Pnrahia's rebellious pupil. The anonymous fool of the Jerusalem Talmud's legend is identified with Jesus of Nazareth. Because of a silly slip of the tongue, his rabbi bans him, and because of an accidental difficulty, he is not pardoned, and therefore abandons his faith. Joshua b. Perahia proclaims a ban with the blowing of four hundred rams' horns according to the Babylonian Talmud model…The insertion of the Christian Messiah's name and the peculiar identification with the dissident pupil in Ben Perahia's company led to a confusion of chronological conceptions and great difficulties for medieval defenders of Judaism, who were obliged to refute hostile accusations and disown the talmudic vilifications of the Christian savior.

Nevertheless, there was no lack of modern attempts to uncover an ancient core in that report that identifies Jesus of Nazareth with Joshua b. Perhia's pupil, relying on the support of Epiphanius, who sets the birth of Jesus in the reign of Alexander (Jannaeus) and Alexandra, that is, in the time of Ben Perhia or Ben Tabai. All these attempts, however, are based on pure delusion. Epiphanius does not contradict the doctrine of the Church and does not, in opposition to deep-seated belief, bring forward the birth of Jesus (the Christian Messiah or some other Jesus). He simply reiterates the claim made by the Church Fathers (e.g. Hippolytus, Eusebius, Jerome) that after the decline of the Hasmonean kingdom, Jacob's blessing of Judah was fulfilled ("The scepter shall not depart from Judah, nor a lawgiver from between his feet, until Shiloh come"; Gen 49:10) as was the count of "seventy weeks" of years according to Daniel (9:24ff.). In their view the redeeming mission of Jesus was thus confirmed.

For Epiphanius, Jannaeus represents the last appearance of a Jewish prince, a true independent ruler wearing a double crown of kingship and priesthood. Upon his death the single rule was divided, quarrels and disturbances split the country until the rise of Herod, who was not of Jewish descent, that is, until the realization of the vision in biblical prophecies. According to this viewpoint, Jerome, too, sees Jannaeus as the priest king, the last legally anointed head of the Jewish people, before "the scepter" departs "from Judah" and the Christian salvation comes, at the end of the "seventy weeks" as foreseen by Daniel. Intending to stress the theological notion, Epiphanius skips the period between the death of Jannaeus and the gospel of Jesus, in order to connect Jannaeus and his offspring with the Herondian era. His entire exegesis contains no trace of a tradition, Jewish or Christian, regarding an unknown Jesus at the time of Joshua b. Perahia. Joshua Efrón, Studies on the Hasmonean Period (E. J. Brill: Leiden, 1987), 158-59.

Back to the review:

Carrier says that there are parallels between Christ and mystery cults, and also between Christ and Romulus (for which Carrier cites Plutarch, Romulus 27-28). One can perhaps quibble on details: there is debate about how or whether Romulus even died, and thus it may be hasty to say that he was resurrected. At the same time, there are parallels: Romulus does ascend to heaven, appear to people thereafter, and talk about a kingdom.

i) What you have in the case of Romulus is not a resurrection but apotheosis. A mortal who's elevated to the pantheon. It's a category mistake to compare the two. These belong to different thought worlds.

ii) Romulus is the legendary founder of Rome. This is national mythology. Political propaganda to retroactively validate the claims of Rome. Romulus was never anything other than a mythological figure.

Wednesday, February 10, 2016

Jesus remembered

Sometimes the Gospels have explicit time-markers. Sometimes they have particles that simply indicate a transition from one scene to the next–without indicating the duration of the interval, or whether that even comes later.

Sometimes there's an intrinsic temporal sequence. The arrest of Jesus precedes his trial, which precedes his crucifixion, which precedes his burial, which precedes his resurrection, which precedes his ascension. Even if there were no time-markers to indicate what's sooner in relation to what's later, it would be self-evident.

But in many cases, all we have is a narrative sequence, which may or may not track a chronological sequence. So what should the reader expect?

One issue is how we envision the process of composition. For instance, do we think the author sat down and manually wrote out the Gospel? If so, that would be a somewhat laborious process. How much would he write at a sitting? Would he write a scene, take a break, then pick up where he left off a day or so later?

Another question is whether he had a mental outline of what he intended to include, and in what order. How much did he have planned out in advance?

But here's a different consideration: suppose, instead of writing it out by hand, he dictated his Gospel to a scribe. That involves a different psychological process. When you tell one or more anecdotes about your life, you generally relay them in the order that you remember them rather than the order in which they occurred.

Think about how old folks reminisce. If you ask them what it was like growing up, they don't proceed in a linear fashion. Rather, they string together the most memorable events growing up–often in no particular order. I daresay we have many memories that we can't place in a relative chronology.

Indeed, this tends to be free association, where one memory triggers a related memory. Commentators often talk about narrative strategy and topical arrangement. But how much of that is actually mnemonic rather than literary?

Suppose John dictated his Gospel to a scribe. Suppose that took place over the course of several weeks. Presumably, John thinks about what he's going to tell the scribe today. He consciously summons his memories of Jesus. Mental images of things that happened at a particular time and place.

No doubt John wants his memoir of Jesus to have some structure and directionality. Have a beginning, middle, and end.

Still, if the Fourth Gospel is a transcript of his recollections of Jesus, there's no antecedent reason we'd expect it to be rigorously chronological. Memories of people you knew pop into your awareness without any temporal sequence.

If the Fourth Gospel is oral history committed to writing, I doubt John was chronologically self-conscious as he tells an anecdote. Presumably, he's not thinking about where the next anecdote should go at the time he's recalling something Jesus said or did. Unlike writing, it's easier to lose your train of thought when dictating unless you concentrate on one thing at a time. If you interrupt an older person who's telling an anecdote, they may well forget where they were. They lose the thread.

Incidentally, this may explain the "epilogue" to John's Gospel. His Gospel seems to have two endings. It apparently ends with chap. 20. Yet that's followed by chap. 21. If, however, John was dictating his Gospel, then that "afterthought" is very understandable. That's how people remember things. They don't have everything before their eyes. Rather, their mind jumps from one recollection to another.

Likewise, that may explain the temple cleansing in Jn 2. Jesus either cleansed the temple once or twice. We can't say for sure. All we have to go by are the Gospels, and they don't number the temple cleansing(s). It's possible that he did so twice. Or it's possible that this was one event, which John's Gospel records in chap 2 because he remembered it on the day he dictated that section of the Gospel.

Gospel harmonization

1. Gospel harmonization may sometimes seem to be an exercise in special pleading. Inerrantists indulge in face-saving harmonizations. Liberals say the real explanation is due to different Gospels using divergent, independent traditions.

2. However, there are problems with the liberal explanation even on its own terms. For one thing, the mainstream view of the Synoptic problem is that Matthew and Luke use Mark as a source. When that's the case, you can't chalk the differences up to independent divergent traditions. Moreover, this isn't a conservative view of the Synoptic problem. Rather, most NT scholars all along the theological spectrum think Matthew and Luke are indebted to Mark.

3. Apropos (ii), scholars often use redaction criticism to account for Synoptic variants. But on that explanation, the difference isn't due to independent divergent traditions, but editorial activity, such as audience adaptation or narrative strategy.

4. Among other things, William F. Buckley was a novelist. He once said that in every novel he wrote he included one major coincidence. Although a coincidence is unlikely, unlikely events happen in real life, so it would be unrealistic if nothing unlikely, nothing coincidental, happened in his plots.

By the same token, it's unlikely that Jesus was anointed twice. But that doesn't mean it didn't happen. Indeed, that doesn't mean there's a presumption against it.

It's not special pleading to think the Lukan anointing is a different event from a somewhat similar event reported in Matthew, Mark, and John. That would be a striking coincidence, but that sort of thing happens in real life.

5. I think it's a worthwhile exercise to produce a chronological life of Christ based on the Gospels. However, I don't view the four Gospels as raw material for reconstructing the life of Christ. These aren't packages which were meant to be torn apart. These were written to be read as integral wholes.

The notion of going behind the text to determine what really happened is invidious. Since, moreover, the Gospels are generally our only source of information, there are inherent limits to harmonization. We can't automatically use one Gospel as the benchmark that controls the direction of harmonization. If we have different accounts of the same event, we can't necessary say which one tells when or where it really took place, while the other represents a topical rearrangement. Sometimes there are narrative clues, but sometimes not. And it doesn't bother me if we can't always sort this out.

6. My general position is different from both Licona's and Lydia's. On the one hand, I don't think Licona is a terribly competent exponent of the position he's promoting. And I don't like how he frames the issue, in terms of Roman bioi as a standard of comparison. In addition, his whole approach is rather flippant.

That said, there's an a priori character to Lydia's position, in terms of how she defines historicity. Essentially dictating to the Gospel authors how they are allowed to narrate history. I don't agree with Lydia's stipulative criteria. Ironically, Lydia's evidentialism is quite presuppositional in its own way.

We need to accept Biblical history as it comes to us. Moreover, the reason the issue of Gospel harmonization crops up in the first place is because we do have variant accounts in the Gospels. It isn't based on comparing the Gospels to Roman bioi.

The very examples that provoke these debates give us reason to make allowance for certain narrative strategies. Furthermore, we have OT counterparts. We have "synoptic" OT accounts. Parallel reports with variants.

7. Lydia raises a valid question regarding the presence or absence of narrative clues that would indicate to the reader when the sequence is topical rather than chronological, when there's narrative compression, &c. That's a valid question, especially in reference to Licona's position.

i) One clue involves parallel accounts. That, in itself, supplies a frame of reference. Comparing and contrasting Biblical accounts of the same events. That clues the reader to take these differences into consideration. The very phenomena that give rise to this discussion provides a backdrop.

ii) But there's also the question of what a reader was entitled to expect. It is reasonable for a 1C reader to presume the sequence is chronological unless there's some literary notice to the contrary? Is it reasonable for a 1C reader to presume the record is unabbreviated unless there's some literary notice to the contrary? I don't think so.

8. To judge by Lydia's discussion of Licona's video presentation (which I haven't watched), there appear to be some similarities between what he is saying and evangelical NT scholars say. In that respect it's not out in left field.

Take the cleansing of the temple. Both Keener, in his commentary on John (1:518), and Block, in his recent commentary on Mark (291n498), think this was a single event, which John transposes. Likewise, both Craig Blomberg, in The Historical Reliability of the Gospels (2nd ed., 216ff.), and Vern Poythress, in Inerrancy and the Gospels (133ff.), regard that a legitimate interpretive option.

Likewise, in reference to the healing of the centurion's son, the explanation that Luke is more detailed, that it was emissaries who spoke on behalf of the centurion, whereas Matthew, through narrative compression, collapses that distinction, is a standard evangelical harmonization. That's defended by scholars like Bock ("Precision and Accuracy"), Blomberg (ibid. 176), and Poythress (ibid. 17ff.). That's the function of spokesmen. And 1C readers would be expected to share that cultural preunderstanding.

I'm not using that as an argument from authority. The fact that I can cite conservative scholars who take that position doesn't make it correct. But I wonder how conversant Lydia is with the landscape of evangelical Biblical scholarship.

Again, it's a good thing to have folks from a different discipline interact with Biblical scholarship. Biblical scholarship can become ingrown and hidebound. It's useful to have a fresh perspective.

9) Regarding the withering of the fig tree, we need to distinguish between what Matthew actually says and what a reader imagines. It's natural for readers to form mental images of what they read. And I think that's a good practice.

So a reader might visualize the fig tree shriveling up right before the disciples' eyes in a matter of moments. That, however, is not what Matthew says. We need to differentiate how we picture the event from how Matthew depicts the event. Matthew's description is much vaguer.

10) Lydia says:

The difficulty is that apparently this same anointing, which John appears to place on the Saturday before the triumphal entry, is quite explicitly stated to have happened two days before the Passover in Mark 14, and Mark is extremely chronological in his telling of the events of Passion Week.

i) Assuming these are chronologically discordant accounts (of the same event), it would be a case of temporal transposition. I think Matthew, Mark, and John refer to the same event. Luke's anointing account refers to a different event.

ii) Since John's account seems to be more firmly grounded in the setting, his would be the chronologically accurate version, while Matthew and Mark transposed it for thematic reasons–unless they didn't know when it actually happened. Events can be related in different ways.

iii) However, as one scholar observes:

The dinner during which Jesus was anointed (Jn 12:2-8) occurred in all probability on Saturday evening…It would be a mistake to conclude from Mt 26:2 ('after two days comes the Passover') and its parallel in Mk 14:1, that Jesus was anointed instead on Tuesday evening…For whereas the chronological marker of Jn 12:1 ('six days before…')is directly related to the anointing (12:2-8), that of Mt 26:2 ('after two days') is directly related to the plot to kill Jesus (26:3-5) and neither Mt 26:6-13 nor Mk 14:3-9 expressly relates the anointing to its context in chronological terms. K. Chamblin, Matthew: A Mentor Commentary (CFP 2010), 2:1270.

11) Lydia says:

For example, if John knowingly shifted Jesus' cleansing of the Temple by three years to the beginning of his ministry (which would seem to be precisely the sort of thing Licona means by "displacement") and no such cleansing took place then, that is a _serious_ failure of historical reliability, and frankly, if you or Licona or anybody else defines "reliability" differently, you can just have your concept, and I'll stick with mine.

But that confounds narrative sequence with chronological sequence. In the Synoptics, the cleansing of the temple is firmly grounded in the narrative setting. By contrast, it doesn't have those chronological connectives in John. It isn't linked to what precedes it or follows it. So readers don't have to right to presume that it must have taken place at that juncture. The narrative itself doesn't make that claim.

12) Lydia says:

The question is just whether Jairus already knew, and said at the outset, that his daughter was dead, or whether he said that she was on the point of dying.

i) For starters, the notion that Matthew's account on the incident reflects narrative compression is a standard evangelical harmonization. That's not just Licona.

ii) In addition, we need to distinguish between direct and indirect discourse. Between what the narrator says and what he quotes a character saying.

Inerrancy doesn't not entail that whatever a character says is true. Inerrancy primarily refers to the narrator.

Inerrancy doesn't mean Jairus is inerrant in how he expressed himself. Jairus wasn't speaking under divine inspiration.

This, in turn, raises the question of how a narrator should quote a speaker. There's a paradoxical sense in which, if someone makes an inaccurate statement, an accurate quote may preserve the inaccuracy. If you're quoting someone, you're not necessarily endorsing what they say. Rather, you're simply reporting what they said. If they made an inaccurate statement, that's what you report.

On the other hand, there might be occasions where, out of charity, a narrator will correct an incorrect statement when quoting a person based on what the person intended to say. Sometimes it's clear what a speaker meant to say, even if he misspoke or expressed himself poorly.

So, when quoting a character, there are occasions when it would be appropriate for the narrator to improve on the original statement. It's not a verbatim quote. Rather, it's what the speaker meant to say, but failed to say. A narrator might clarify what he meant by restating it. That's an editorial judgment call.

“Traditionalist” Roman Catholics anticipate the death of “Pope Francis” with trepidation

|

| “It’s

no good being pope. They’re planning already for my death!” |

Watch Out - Great Editorial Manoeuvres Signal Cardinal Tagle

Today, when, in the ecclesisastical milieux opposed to the Bergoglian establishment, the "candidacy" of Cardinal Tagle, Archbishop of Manila, is mentioned, the subject is barely worthy of attention. And yet, the great editorial manoeuvres have started with him!

Vaticanist Cindy Wooden, who directs Catholic News Service, has published his biography, Luis Antonio Tagle: Leading by Listening (Liturgical Press, 2015). Qualified as a "Cardinal of the Poor", a man who listens, a man of dialogue, he is presented as being at the edge of the new evangelization. The book is being translated in several languages, including in French. In Italy, always on the same theme of "the man of evangelization" and "the poor", yet another book on Cardinal Tagle is to appear, "Dio non dimentica i poveri. La mia vita, la mia lotta, le mie speranze" (God does not forget the poor: My life, my struggle, my hope) [Editrice Missionaria Italiana].

Tagle, an intelligent man, with no exceptional personality, young (not yet 59), staunchly liberal, is the ideal character to solidify the hopes of all those who do not wish that the pontificate of Pope Francis be a simple parenthesis. In a previous article of February 9, 2015, we wrote here that this son of the Manila upper class had obtained his university degrees in the United States (on the theme of Episcopal Collegiality), and had taken part in the works of the team that had supervised the monumental History of Vatican II, edited by the ultra-progressive School of Bologna (Giuseppe Alberigo and Alberto Melloni). He had as his mentor Father Catalino Arevalo, Filipino Jesuit, who was acknowledged by the Federation of Asian Bishops' Conferences as the "Father of Asian Theology", a local version of Liberation Theology. Fr. Catalino Arevalois a disciple of Jürgen Moltmann and of his "trinitarian theology", that considers the Trinity as an "event", fabricated, to say it in a simple way, by the event of the Cross, where God made Jesus his "Son" and obtained his "identity" as "Father". It was Moltmann's disciple that Benedict XVI, always particularly sensitive to academic relationships, made Archbishop of Manila in 2011 and Cardinal in 2012.

An enthusiastic elector of Pope Francis in 2013, he met him again at the time of his apostolic voyage to the Philippines in January 2015. Francis placed him in front of him, to the point that numerous journalists started treating him as the "heir". One of his most powerful supporters, the Honduran cardinal Rodriguez Maradiaga, coordinator of the Council of 9 Cardinals charged by the Pope of proposing ideas for the famous reform of the Curia had him elected president of Caritas Internationalis on May 14 2015, with a majority of 91 over 133 representatives, as a defender of the marginalized.

The liturgical ideas of Cardinal Tagle? They are well expressed by his predecessor, Cardinal Gaudencio Rosales, Emeritus of Manila, who, during a mass presided by Cardinal Tagle last January 26, at the 51st Internationzal Eucharistic Congress, which took place in Cebu, Philippines, encouraged to "make Eucharist by freeing oneself from the rituals".

A Co-President of the two last Assemblies of the Synod of Bishops, in 2014 and 2015, he had made himself known, at a press conference in the Holy Office Press Office, by these words: "In this Synod, the Spirit of Vatican II has made itself manifest in the Fathers." In her book, Cindy Wooden presents the Cardinal of Manila as a man of the future, one of the great future pastors of the Church. What Saint Charles Borromeo was for the Council of Trent, Luis Antonio Tagle would be for the Vatican II: the example of a new way of governing in the Church. It is, anyway, the image that is being desperately "put on sale"...

Further thoughts on Tuggy's challenge

"Further Thoughts on Tuggy’s Challenge" by Prof. James Anderson.

Tuesday, February 09, 2016

N.H.

Last time I checked Real Clear Politics, which had the tally at 84%, NH proved to be a better night for the liberal/moderate candidates (Trump/Kasich/Jeb) than the more conservative candidates (Cruz, Rubio). That's not surprising. NH is a blue state. It says a lot about NH voters that they like Trump so much. Unfortunately, what it says about them isn't good.

Cruz survives. Rubio was hurt.

Christie may have hurt Rubio without helping himself.

Unless the pecking order changes with additional returns, Jeb couldn't beat Cruz in a state that ought to favor a candidate like Jeb over a candidate like Cruz. Maybe Jeb can continue to limp along.

Rubio needs to up his game to stay in the game.

At the moment it's probably a two-man race between Trump and Cruz, heading into SC.

Are tu quoque arguments fallacious?

Some pop internet sources classify the tu quoque argument as a fallacy, but that's erroneous:

I am using ad hominem in the way Peter Geach uses it on pp. 26-27 of his Reason and Argument (Basil Blackwell 1976):This Latin term indicates that these are arguments addressed to a particular man -- in fact, the other fellow you are disputing with. You start from something he believes as a premise, and infer a conclusion he won't admit to be true. If you have not been cheating in your reasoning, you will have shown that your opponent's present body of beliefs is inconsistent and it's up to him to modify it somewhere.As Geach points out, there is nothing fallacious about such an argumentative procedure. If A succeeds in showing B that his doxastic system harbors a contradiction, then not everything that B believes can be true.

http://maverickphilosopher.typepad.com/maverick_philosopher/2015/11/the-problem-of-evil-and-the-argument-from-evil.html

Exploring the Exodus

1. Over at Debunking Christianity, apostate atheist Hector Avalos has a long review of Patterns of Evidence. I won't have much to say in response to Avalos, since his post is not a direct attack on the Exodus itself, but on a film about the Exodus. At the end of this post I will comment on one of his statements.

I haven't seen Patterns of Evidence. But from what I've read about it, I'm concerned that the film seems to be predicated on a false premise:

The operating assumption is that if the Exodus was a real event, there ought to be hard evidence for that event. And from reviews I've read, the film's solution is that scholars are looking for evidence within the wrong period.

Assuming that's accurate, it's a misguided way to frame the issue. The "Exodus" is, itself, something of an umbrella term for (A) the period in which Israelites were slaves in Egypt, followed by (B) their miraculous deliverance from Egypt, followed by (C) their "40" year sojourn in the Sinai desert, followed by (D) the "Conquest" of Israel.

2. We need to begin with a realistic understanding of what kind of physical evidence we'd expect to be available at this late date. As Edwin Yamauchi noted, in The Stones and the Scripture:

• Only a fraction of the world’s archaeological evidence still survives in the ground.

• Only a fraction of the possible archaeological sites have been discovered.

• Only a fraction have been excavated, and those only partially.

• Only a fraction of those partial excavations have been thoroughly examined and published.

• Only a fraction of what has been examined and published has anything to do with the claims of the Bible!

3. Regarding A-B:

i) Genesis and Exodus never name the Pharaohs who interacted with Moses and Joseph. That, itself, limits our ability to date the chain of events. We don't even know whose royal records to consult, assuming they're available. We don't know which Pharaonic tomb to look into. That tomb may not have been discovered or excavated.

ii) Even if we knew where to look, Pharaonic tombs don't broadcast the domestic and foreign policy failures of the establishment.

iii) The Israelites resided in the Nile Delta. By definition, that's a flood zone. Do we really think their mud huts will survival millennia of erosion?

4. Regarding C:

i) The Sinai desert is about the size of West Virginia.

ii) What physical evidence we'd expect to survive depends, in part, on the number of Israelites. Estimates vary. In his commentary, I think Douglas Stuart reasonably estimates their number at 28,800-36,000 (p302).

iii) They only resided in the Sinai for a period of about 40 years, during the 2nd millennium BC.

iv) They didn't settle down. Didn't build fortified cities with stone walls, houses, and public facilities. Rather, they were nomads, living in tents and moving from place to place.

v) Even if they had some hard artifacts, like metal tools, they'd take that with them into the Promised Land rather than leaving it behind.

vi) Moreover, they were hardly the only people-group to trek through the Sinai. Even if they did leave behind trace evidence, how would we be able to distinguish that from other nomadic groups in the Sinai, like the Bedouin? (I don't necessarily mean there were Bedouin at that time and place, but groups like the Bedouin.)

5. Regarding D:

i) Attacks on the historicity of the Conquest are typically based on misreading what Joshua and Judges actually claim. As one commentator notes:

The fact is that the book of Joshua does not claim that the Israelites caused widespread destruction of cities; in fact, it explicitly denies this (Josh 11:13). Joshua speaks of cities being taken and people (especially kings) being killed, but "only three cities–Jericho, Ai, and Hazor–are said to have been burned" (Josh 6:24; 8:28; 11:11,13). Furthermore, some areas seem to have been taken by something more like accommodation (or interpretation) than conquest (e.g., Gideon, Josh 9; Shechem, Josh 24:1,25; Gen 34). Finally, there is abundant evidence in the biblical record, especially in Judges, of Israelites intermarrying with Canaanites and worshipping their gods…It should hardly surprise us, therefore, if in the material remains of the period Israelites are virtually indistinguishable from Canaanites. B. Webb, The Book of Judges (Eerdmans 2012), 10.

ii) Avalos says:

Mahoney never addresses the seemingly blatant contradiction that Jabin and Hazor are supposed to have been exterminated completely in Joshua 11:1, 10, and yet there is Jabin king of Hazor AFTER the death of Joshua (See Judges 1:1) in Judges 4:2.

Apologists have attempted to explain this away by saying that there were two different Jabins. However, Judges has at least one other instance where it simply repeats a story from Joshua (compare Judges 1:11-15 with Joshua 15:15-19)

Therefore, editorial problems probably better explain the occurrence of Jabin in Judges 4. Otherwise, one would have to suppose that after a complete destruction of both city and people, Hazor rose again within a few years, and installed another king Jabin. The archaeological evidence is certainly lacking for that.

iii) But as one scholar notes:

The appearance in Joshua-Judges of two kings with the name Jabin is no more a "doublet" than two Niqmads (II and III) and two Ammishtamrus (I and II) in Ugarit, or two Suppiluliumas (I and II), two Mursils (II and III), and two Tudkhalias III and IV) of the Hittites, or two pharaohs (Amenophis (III and IV), Sethos (I and II), and Ramesses (I and II) in Egypt–all these in the fourteenth and thirteenth centuries. K. Kitchen, On the Reliability of the Old Testament (Eerdmans 2003), 184-85.

As another scholar notes:

Jabin was probably a royal title (like "Pharaoh" for the kings of Egypt). Joshua had defeated another "Jabin" at Hazor almost one hundred years earlier (Josh 11:1-11). Verses 23-24 probably refer to the final destruction of a resurgent Hazor in the thirteenth century, as attested (on at least one reading of the data) by the archeological remains there. B. Webb, ibid., 180.

iv) Notice that this isn't "within a few years," but about a century later. A lot can happen in a century.

In addition, there's a reason why some sites were settled in the first place. They may have access to fresh water for drinking, fishing, or irrigation. They may be located along trade routes.

That means that even when a site is destroyed by invaders, it remains an appealing location, for all the reasons that made it a magnet for the original settlers. So it's not surprising that it will be repopulated at a later date. Prime real estate is always desirable.

Monday, February 08, 2016

Mantrap

A stock objection to Calvinism is that it implicates God in evil because God "causes" or "determines" evil. Let's consider natural evil from the standpoint of freewill theism. Now, I think it's reasonable to claim that physical determinism governs nature at the macro level.

Depending on your interpretation of quantum physics, subatomic events are either statistical or deterministic. But even if you think they are statistical, that doesn't seem to transfer to the macro world.

According to Christian theology, there's an interplay between personal agents and natural processes. What the natural order does when left to itself is deterministic, absent outside intervention by a personal agent. (The subatomic order might be an exception.)

In that respect, nature is like a machine. If I create a mantrap, it's the trap that catches or kills the poacher or trespasser. Yet the trap was only doing what I designed it to do. It's not the mantrap, but me, that's responsible for the outcome.

Every so often we read a news report about someone who put a venomous snake in the mailbox of his enemy. When his enemy reaches into the box to get his mail, he is bitten by the snake.

Now, it was the snake, and not the culprit, that bit the man. But, of course, we still hold the man who put the snake in the mailbox responsible for the snakebite.

It isn't even a sure thing that his enemy will die of snakebite. It might be a dry bite. Or he might receive antivenom in time to save his life. Even so, the culprit will be charged with attempted murder.

Suppose it's the enemy's 10-year-old son who checks the mailbox that day, only to be bitten. The culprit didn't intend to harm or kill his enemy's son. But, of course, that hardly exonerates him. "I'm sorry, your Honor. I didn't mean to kill the boy. That was an accident. His dad was my target!"

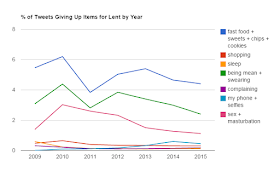

It’s time to think about Ash Wednesday and Lent

|

| Giving things up for the Kingdom? |

Such suggestions among Christians border on the ridiculous. We should remember Paul’s admonitions, such as:

Let me ask you only this: Did you receive the Spirit by works of the law or by hearing with faith? Are you so foolish? Having begun by the Spirit, are you now being perfected by the flesh? Did you suffer so many things in vain—if indeed it was in vain? Does he who supplies the Spirit to you and works miracles among you do so by works of the law, or by hearing with faith—just as Abraham “believed God, and it was counted to him as righteousness”? Galatians 3:2-6)

And:

If with Christ you died to the elemental spirits of the world, why, as if you were still alive in the world, do you submit to regulations— “Do not handle, Do not taste, Do not touch” (referring to things that all perish as they are used)—according to human precepts and teachings? These have indeed an appearance of wisdom in promoting self-made religion and asceticism and severity to the body, but they are of no value in stopping the indulgence of the flesh (Colossians 2:20-23).

Instead, Ash Wednesday is a 10th century invention, and not one “Lenten” practice can be traced to the New Testament. The list here, compiled by Yves Congar in his “The Meaning of Tradition”, places many of these rituals well into the fourth century and later:

— The Lenten fast (Irenaeus, Jerome, Leo)

— Certain baptismal rites (Tertullian, Origen, Basil, Jerome, Augustine)

— Certain Eucharistic rites (Origen, Cyprian, Basil)

— Infant baptism (Origen, Augustine)

— Prayer facing the East (Origen, Basil)

— Validity of baptism by heretics (pope Stephen, Augustine)

— Certain rules for the election and consecration of bishops (Cyprian)

— The sign of the cross (Basil, who lived 329-379)

— Prayer for the dead (note, this is not “prayers to the dead) (John Chrysostom)

— Various liturgical fests and rites (Basil, Augustine)

From Yves Congar, in his “The Meaning of Tradition,” (and derived from his scholarly “Tradition and Traditions” and a textbook for Roman Catholic seminarians), (pg. 37).

Again, while such practices as Lenten fasts and the sign of the cross are still practiced, many of these “apostolic traditions” – really those extending earlier than the 4th century – such as prayer facing east, and Cyprian’s rules for electing and consecrating bishops, actually find themselves in the dustbin of history.

Even those for which there is attestation became exaggerated over time. The “Lenten Fast” mentioned with respect to Irenaeus, above, for example, originally only was “40 hours”:

Closer examination of the ancient sources, however, reveals a more gradual historical development. While fasting before Easter seems to have been ancient and widespread, the length of that fast varied significantly from place to place and across generations. In the latter half of the second century, for instance, Irenaeus of Lyons (in Gaul) and Tertullian (in North Africa) tell us that the preparatory fast lasted one or two days, or forty hours—commemorating what was believed to be the exact duration of Christ’s time in the tomb. By the mid-third century, Dionysius of Alexandria speaks of a fast of up to six days practiced by the devout in his see; and the Byzantine historian Socrates relates that the Christians of Rome at some point kept a fast of three weeks. Only following the Council of Nicea in 325 a.d. did the length of Lent become fixed at forty days, and then only nominally. Accordingly, it was assumed that the forty-day Lent that we encounter almost everywhere by the mid-fourth century must have been the result of a gradual lengthening of the pre-Easter fast by adding days and weeks to the original one- or two-day observance. This lengthening, in turn, was thought necessary to make up for the waning zeal of the post-apostolic church and to provide a longer period of instruction for the increasing numbers of former pagans thronging to the font for Easter baptism. Such remained the standard theory for most of the twentieth century.

We simply should not adopt fourth century practices as if it enables us to repent better than or more sincerely than simply to bow our heads and “with confidence draw near to the throne of grace, that we may receive mercy and find grace to help in time of need.”

Rubio and Cruz

1. Some voters act as though supporting a candidate means defending everything they say and do. I notice that some Cruz supporters excuse everything he every said or did, or unquestioningly accept his ex post facto explanations. That's very credulous.

Rational voters can separate out defending someone's candidacy from blanket support for whatever they say or do. It's possible to support someone's candidacy despite disagreement with one or more of their positions or policies.

Indeed, it's important to reserve the right to criticize positions/policies of a candidate you otherwise support. I don't issue any candidate a blank check.

For instance, I might support a candidate even though I disagree with some of his policies. That doesn't necessarily mean I give up those issues. If he becomes president, it's still possible to block those particular policies at a legislative or judicial level. It becomes a question of when and where to fight.

2. Some voters raise fake, frivolous objections to a rival candidate. This is where they are reaching for anything they can use against the rival candidate. These are not objections they consistently raise. If their favorite candidate did the same thing, they'd give him a pass. Or if it were a different election cycle, they might swap those out for different objections. For instance, opponents of Rubio complain about his missed votes. They say he's not doing the job he was paid to do. But there are several problems with that complaint:

i) There's more to the job of a legislator than showing up to vote. His job includes meeting with constituents. Serving on committees and subcommittees. Intercede with other gov't agencies on behalf of his constituents.

ii) Many votes are just symbolic votes. Unless his vote is required for passage of a bill, or for the bill to pass by a veto-proof majority, missing a vote is not intrinsically significant.

iii) Let's compare Rubio's missed votes to Cruz:

Rubio:

14.1%

https://www.govtrack.us/congress/members/marco_rubio/412491

Cruz

13.8%

https://www.govtrack.us/congress/members/ted_cruz/412573

So Rubio misses votes 0.3% more often than Cruz. Clearly that's a frivolous objection.

3. Another phony issue is that he's too scripted in debates. But when you are limited to 30-60 second answers, you need to have compact, prepared answers to predictable questions.

4. A basic problem with raising phony objections is that it gives equal weight to frivolous objections and serious objections. But that's a way of saying serious issues don't matter. If you treat frivolous objections and serious objections equally, then you really don't care about the issues. You really don't care about ideology. But I do.

Here are some serious, substantive criticisms Rubio:

If you wish to find fault with Rubio, talk about something like that.

5. There are roughly two considerations:

i) Is Republican candidate A better or worse than Republican candidate B?

ii) Is Republican candidate A (B, C) better than the Democrat candidate?

You could have two Republican candidates who are both better than the Democrat; one Republican candidate is better than another, but the better candidate is less electable. So you have a twofold comparison; two considerations you need to balance: Which is worse? for the Democrat to win, or for a Republican to win, who's better than the Democrat, but worse than one (or more) of his Republican rivals (who have little chance of winning)?

I know some Christians bristle at those comparisons, but reality constrains our field of action. Suppose I said that if you wish to draw water from a well, you should use a bucket rather than a pasta strainer. Some Christians would respond by saying "That's pragmatic! That's worldly wisdom!"

6. Oftentimes, the debate is cast in terms of Cruz as the intrinsically better candidate, but we must settle for Rubio because Cruz is unelectable. An unfortunate, but necessary compromise. One problem I have with that way of framing the issue is that I not only have some genuine reservations about Rubio, but I have some genuine reservations about Cruz. I doubt he's quite the knight in shining armor that some of his supporters imagine him to be.

i) Take his position on SSM. In an interview, shortly after Obergefell, he said gov't officials should simply ignore the ruling:

I like that. But I can't help noticing that his initial reaction to Obergefell wasn't that hardline. Initially, he proposed a Constitutional amendment:

I have a default suspicion about Republicans who propose Constitutional amendments in the culture wars. I think that's often a decoy. It's a lengthy process that usually goes nowhere. So it's a proposal that doesn't cost the politician anything. A diversionary tactic creating the pretense that a politician has taken meaningful action, when it deflects attention away from meaningful action. Placating social conservatives with symbolism.

I'm also curious about the timing. Between his initial, weaker response, and his later, tougher response, Cruz's mentor, Robert George, came out with a public statement saying officials should disregard the ruling.

Right after that, Cruz came out with a public statement saying officials should disregard the ruling. Hmm. Is that just coincidental? Or was Cruz waiting to see how other conservative opinion makers-would respond, then struck a more confrontational rhetorical pose after they did? Is this putting a wet finger to the wind? Did he sense that his first response might be perceived as too weak?

But that's not all. The Lawrence decision laid the groundwork for Obergefell. If you wanted to oppose SSM, it would be more strategic to draw the battle lines sooner, before the homosexual lobby got so much momentum. And Cruz had an ideal opportunity to do so. The Lawrence decision involved a Texas anti-sodomy law, and Cruz was Texas attorney general at the time. He was uniquely positioned to right that battle. Yet he didn't get involved, and there's prima facie evidence that his inaction might be related to his courting gay donors.

http://www.bloomberg.com/politics/articles/2015-04-29/ted-cruz-anti-gay-marriage-crusader-not-always

7. Then there's his position on illegal immigration. There's prima facie evidence that he's shifted position for political expediency:

At one point Cruz proposed an amendment to legalize immigrants, but deny them citizenship, although he now claims that was a poison pill.

However, one can easily see legalization as part of a long-range strategy. If it's too controversial to begin with outright naturalization, you break it down into increments. You lead with legalization as a first step, to gain a foothold. Having achieved that, you then complain about how arbitrary and unfair it is for immigrants who are here legally to be denied a chance to become citizens.

8. Recently, Cruz opposed draft registration for women:

Although I agree with him on the merits, his statement misses the point. Liberals say women can do anything a man can do. So this is calling their bluff. Right now we have a double standard. This is a way of forcing liberals to be consistent–and make them pay a political price for consistency.

9. Finally, some conservatives seem to be schizophrenic about the value of an Ivy League education. They usually say political correctness has ruined the humanities at Ivy League institutions. Students are indoctrinated in sheer propaganda. Liberal ideology is at war with history and science. You'd get a much better education at a Christian college like Patrick Henry.

But then some of them drool over Cruz's Ivy League resume. That suggests a conservative inferiority complex. Is a candidate who attended Harvard and Princeton presumptively better than a candidate (Rubio) who attended a state college on a football scholarship?