Pages

Saturday, September 28, 2013

Breaking Bad

http://godawa.com/movieblog/breaking-bad-yes-virginia-original-sin/

http://godawa.com/movieblog/walking-dead-zombies-god-makes-us-human/

Review of “The Reformation Made Easy”

|

| The Reformation Made Easy |

http://reformation500.com/2013/09/28/the-reformation-made-easy/

I would say that it goes a long way to doing that, but there is so much information to digest regarding the Reformation, that this book may make the Reformation ‘easier’ to comprehend, but still not quite ‘easy.’ From Wycliffe to Hus to Luther to Tyndale to Henry the Eighth, there’s a whole lotta history in this movement called the “Reformation” (and some would prefer the term “Reformations” because of the variety of ways it played out in various places in Europe). This book tries to make sense of it all….

Whatever your perspective on the Reformation, or Christianity in general, this book is an excellent short overview of the major events and personalities in this great movement of God, which is still shaping the world today.

Keep in mind that we’re in Reformation Season – just over a month away from the 496th anniversary of the Reformation!

There’s no such thing as a good pope

|

| No such thing as a good pope |

Don Roberto – Fr Neuhaus also said this: “One cannot draw a neat and uncontested historical line between the apostolic “primacy” of St. Peter and the primacy of the current pope in Rome. But there is a clear line of apostolic authority. Clearer, at the very least, than any other line can be drawn” (from “Catholic Matters”, pgs 18-19).

In both cases, there is not “a clear line” – neither to Peter, nor to “apostolic authority”. The “unclear line” to “apostolic authority” is something that worked for Irenaeus vs the Gnostics in the 2nd century; there is no hint from him or anyone else that what worked in the past was to be a “system” of “succession” that was going to “guarantee” authority for all time. Regarding the “unclear line” extending from Peter to Damasus, it is not only “unclear”, but nonexistent. [And anyone who’s studied in a seminary ought to be familiar with this history].

Is ID science?

Many people argue intelligent design (ID) isn't science.

I'm not an ID theorist. Nor am I affiliated in any way with the ID movement. So I don't speak with any sort of authority on this issue. And it's not necessarily a hill I'd be willing to die on. Rather, this is just my two cents' worth, which may be all it's worth.

Who made God?

Who or what made God?

This is a common question. There have been many solid responses to this question. Not only by sophisticated scholars, but by many sophisticated laypeople too. Many bloggers and commenters have likewise provided better responses than I can muster.

But, FWIW, if anything, here's my quick response:

- The truth is most thinkers believe there's some entity that's fundamental to the entire universe.

For example, Carl Sagan famously said, "The cosmos is all that is or was or ever will be."

Likewise, many scientists tell us it's ultimately all about mass-energy.

Stephen Hawking said in The Grand Design:

Because there is a law such as gravity, the universe can and will create itself from nothing. Spontaneous creation is the reason there is something rather than nothing, why the universe exists, why we exist. It is not necessary to invoke God to light the blue touchpaper and set the universe going.

Other scientists posit other fundamentals like quantum fluctuations or superstrings (e.g. M-theory).

And these aren't all mutually exclusive to one another. They can overlap.

But my point is these thinkers and scientists have in mind some fundamental entity or entities to explain the whole of existence. Yet, one could easily ask, if the cosmos is what's fundamental, then who or what made the cosmos? How did the cosmos make itself? How has it always just existed?

If mass-energy is what's fundamental, then who or what made mass-energy? Where did mass-energy come from? How can mass-energy make itself? How has it always just existed?

If a certain set of physical laws are what's fundamental, then who or what made these physical laws? From whence did they come? How have they always just existed?

And so and so forth.

- As I mentioned above, others have better answers. For example, William Lane Craig has said (Reasonable Faith, 3rd edition):

Something that exists eternally and, hence, without a beginning would not need to have a cause. This is not special pleading for God, since the atheist has always maintained the same thing about the universe: it is beginningless and uncaused. The difference between these two hypotheses is that the atheistic view has now been shown to be untenable.

And:

God didn't come from anywhere. He is eternal and has always existed. So he doesn't need a cause. But now let me ask you something. The universe has not always existed but had a beginning. So where did the universe come from?

Friday, September 27, 2013

What is mature creation?

The principle of parsimony

The view that simplicity is a virtue in scientific theories and that, other things being equal, simpler theories should be preferred to more complex ones has been widely advocated in the history of science and philosophy, and it remains widely held by modern scientists and philosophers of science. It often goes by the name of “Ockham’s Razor.” The claim is that simplicity ought to be one of the key criteria for evaluating and choosing between rival theories, alongside criteria such as consistency with the data and coherence with accepted background theories. Simplicity, in this sense, is often understood ontologically, in terms of how simple a theory represents nature as being—for example, a theory might be said to be simpler than another if it posits the existence of fewer entities, causes, or processes in nature in order to account for the empirical data. However, simplicity can also been understood in terms of various features of how theories go about explaining nature—for example, a theory might be said to be simpler than another if it contains fewer adjustable parameters, if it invokes fewer extraneous assumptions, or if it provides a more unified explanation of the data.There are many ways in which simplicity might be regarded as a desirable feature of scientific theories. Simpler theories are frequently said to be more “beautiful” or more “elegant” than their rivals; they might also be easier to understand and to work with. However, according to many scientists and philosophers, simplicity is not something that is merely to be hoped for in theories; nor is it something that we should only strive for after we have already selected a theory that we believe to be on the right track (for example, by trying to find a simpler formulation of an accepted theory). Rather, the claim is that simplicity should actually be one of the key criteria that we use to evaluate which of a set of rival theories is, in fact, the best theory, given the available evidence: other things being equal, the simplest theory consistent with the data is the best one.Many scientists and philosophers endorse a methodological principle known as “Ockham’s Razor”. This principle has been formulated in a variety of different ways. In the early 21st century, it is typically just equated with the general maxim that simpler theories are “better” than more complex ones, other things being equal. Historically, however, it has been more common to formulate Ockham’s Razor as a more specific type of simplicity principle, often referred to as “the principle of parsimony”...However, a standard of formulation of the principle of parsimony—one that seems to be reasonably close to the sort of principle that Ockham himself probably would have endorsed—is as the maxim “entities are not to be multiplied beyond necessity”. So stated, the principle is ontological, since it is concerned with parsimony with respect to the entities that theories posit the existence of in attempting to account for the empirical data. “Entity”, in this context, is typically understood broadly, referring not just to objects (for example, atoms and particles), but also to other kinds of natural phenomena that a theory may include in its ontology, such as causes, processes, properties, and so forth.It is important to recognize that the principle, “entities are not to be multiplied beyond necessity” can be read in at least two different ways. One way of reading it is as what we can call an anti-superfluity principle (Barnes, 2000). This principle calls for the elimination of ontological posits from theories that are explanatorily redundant.Mill also pointed to a plausible justification for the anti-superfluity principle: explanatorily redundant posits—those that have no effect on the ability of the theory to explain the data—are also posits that do not obtain evidential support from the data. This is because it is plausible that theoretical entities are evidentially supported by empirical data only to the extent that they can help us to account for why the data take the form that they do. If a theoretical entity fails to contribute to this end, then the data fails to confirm the existence of this entity. If we have no other independent reason to postulate the existence of this entity, then we have no justification for including this entity in our theoretical ontology.When the principle of parsimony is read as an anti-superfluity principle, it seems relatively uncontroversial. However, it is important to recognize that the vast majority of instances where the principle of parsimony is applied (or has been seen as applying) in science cannot be given an interpretation merely in terms of the anti-superfluity principle. This is because the phrase “entities are not to be multiplied beyond necessity” is normally read as what we can call an anti-quantity principle: theories that posit fewer things are (other things being equal) to be preferred to theories that posit more things, whether or not the relevant posits play any genuine explanatory role in the theories concerned (Barnes, 2000). This is a much stronger claim than the claim that we should razor off explanatorily redundant entities. The evidential justification for the anti-superfluity principle just described cannot be used to motivate the anti-quantity principle, since the reasoning behind this justification allows that we can posit as many things as we like, so long as all of the individual posits do some explanatory work within the theory. It merely tells us to get rid of theoretical ontology that, from the perspective of a given theory, is explanatorily redundant. It does not tell us that theories that posit fewer things when accounting for the data are better than theories that posit more things—that is, that sparser ontologies are better than richer ones.Another important point about the anti-superfluity principle is that it does not give us a reason to assert the non-existence of the superfluous posit. Absence of evidence, is not (by itself) evidence for absence.Consider the following list of commonly cited ways in which theories may be held to be simpler than others:

- Quantitative ontological parsimony

(or economy): postulating a smaller number of independent entities, processes, causes, or events.

- Qualitative ontological parsimony

(or economy): postulating a smaller number of independent kinds or classes of entities, processes, causes, or events.

- Common cause explanation

: accounting for phenomena in terms of common rather than separate causal processes.

- Symmetry

: postulating that equalities hold between interacting systems and that the laws describing the phenomena look the same from different perspectives.

- Uniformity

(or homogeneity): postulating a smaller number of changes in a given phenomenon and holding that the relations between phenomena are invariant.

- Unification

: explaining a wider and more diverse range of phenomena that might otherwise be thought to require separate explanations in a single theory (theoretical reduction is generally held to be a species of unification).

- Lower level processes

: when the kinds of processes that can be posited to explain a phenomena come in a hierarchy, positing processes that come lower rather than higher in this hierarchy.

- Familiarity (or conservativeness)

: explaining new phenomena with minimal new theoretical machinery, reusing existing patterns of explanation.

- Paucity of auxiliary assumptions

: invoking fewer extraneous assumptions about the world.

- Paucity of adjustable parameters

: containing fewer independent parameters that the theory leaves to be determined by the data.http://www.iep.utm.edu/simplici/

Thursday, September 26, 2013

Transitive memory

Critics often say the Gospel writers couldn't remember what happened. Now, that simply refuses to take inspiration into account.

Animal mortality

If the image of God's ultimate cosmic peace (among other things) is that the lion lies down with the lamb, did the lion lie down with the lamb before the fall?

Sing, O heavens, for the Lord has done it; shout, O depths of the earth;break forth into singing, O mountains, O forest, and every tree in it! (44:23).

“For you shall go out in joy and be led forth in peace;the mountains and the hills before you shall break forth into singing, and all the trees of the field shall clap their hands.

Instead of the thorn shall come up the cypress; instead of the brier shall come up the myrtle;and it shall make a name for the Lord, an everlasting sign that shall not be cut off (55:12-13).

Dion Astwood

I think the issue needs answering, but I don't find the criticisms in the article that compelling. Jesus made wine from water, that is a creative event.

It is not that God could not create new kinds of creatures after the 6 days, it is that it does not appear that he did.

Modifying creatures post fall, even genetically, fits with YEC.

The world was cursed and that means changes. Thorns (I believe) are mutated leaves, but that God directed that on a global scale fits in a with a curse.

Further, it is not that human death is assumed to apply to animal death thus animals were not carnivorous, it is that the animals were vegetarian as they are described. The author is incorrect about many carnivores, they can live even now on a vegetarian diet including felines, canines.

He is also probably incorrect about the vampire bat.

It is also not ad hoc. Plants died. Why does Steve think that ants need to be classified with dogs and not plants, or fungi, or sponges, or bacteria.

Prelapsarian bacteria certainly died.

Sponges are classified in animalia though we would not consider them dying prior to the Fall, nor even now. Scripture suggests that death relates to the soul and breath

thus breathing is a quality of an animal who can die, not Steve's presumption of how he thinks they must be classified.

His critique would be better if he were more well read

and interacted on a deeper level.

"So there is some level of death (or predation and Steve's feelings about anteaters and ants doesn't really cut it."

"In terms of subsequent creation, I don't see it as a necessary problem."

"Thorns are new…"

"and this can either be targeted genetic change by God in a pre-existent kind, permitted genetic change (which continually happens with new disease) or creating a new kind."

The poor argument from poor design

Here is a helpful response from David Snoke on the argument from poor design:

A standard objection to the argument for design is the "Panda's Thumb" argument – if we look at some living systems, they appear to have instances of poor design. Does this imply that God cannot have designed it?A quantitative standard of design helps in understanding this issue. Suppose I look at a Mercedes-Benz, and decide that the hubcaps are not aerodynamic enough. Should I conclude that the Mercedes-Benz is not a designed system? Or should I simply say that it is designed but does not have the highest possible level of design?

In the case of the Mercedes-Benz, perhaps I have missed some other function of the hubcaps. For example, perhaps they are designed for good looks instead of aerodynamics. In the same way, some authors have made much of the poor design of certain living systems without taking into account their other possible functions in a larger system. For example, peacock tails may make peacocks less efficient, but they have the function of pleasing people. Shade trees convert sunlight less e?ciently than algae, but shade trees provide shade for humans, and algae doesn't.

It is possible for a system to have undetected design. If we do not observe the function for which something is designed, then we will not see its functional dependence on anything. A young child looking at a piece of scientific equipment designed to create nanosecond digital pulses may see nothing but a box with blinking lights and not see any function at all. We can therefore talk about "detected design." If we see no design, we cannot prove that it is undesigned, we can only say that we see no evidence of design. With a quantitative measure of design, we may also say that we see only a certain degree of design.

As Augustine of Hippo argued, no thing but God can be perfect in every way. Therefore every created thing has "imperfections" to some degree. We therefore can speak of a heirarchy of design, from inanimate objects to "lower" life forms to "higher" ones, with increasing quantitative measure of design. This is warranted, for example, by the narrative of Genesis 1, which sets mankind over animals, animals over plants, and plants over the rest. Jesus also said, "Are you not much more valuable than they?"

Finding something further down in degree of design does not imply that no thing has design. In the same way, finding a simple little ditty written by Mozart does not mean he was a poor composer. People make various things for various uses, and there is no logical resaon why God could not do the same.

We must also distinguish between poor design and systems with good design but which have purposes that we do not like. A shark is a well designed killing machine. This raises the question of the problem of evil, which is a separate question. A well-designed, destructive system does not imply the lack of existence of design. It may imply a well-designed instrument of wrath.

Wednesday, September 25, 2013

Thorns and thistles, God's new bells and whistles

The context for my post is Steve's post here as well as a subsequent thread over on Bnonn Tennant's Facebook wall where Dr. Dion Astwood weighed in. (To lay out my cards, my own broad position is I incline toward a mature creation, but I'm open to progressive creationism.)

Dion Astwood said:

Thorns are new and this can either be targeted genetic change by God in a pre-existent kind, permitted genetic change (which continually happens with new disease) or creating a new kind.

My response:

- Hm, "creating a new kind"? So, at the Fall, God got rid of all the vegetarian lions and created new carnivorous lions to replace them?

- Also, per Isa 65:25: "The wolf and the lamb shall graze together; the lion shall eat straw like the ox, and dust shall be the serpent’s food. They shall not hurt or destroy in all my holy mountain, says the Lord."

If we take this literally, then I guess in the Millennium God will re-replace the carnivorous lions with vegetarian lions?

- If, post-Fall, "thorns are new," and if there are "creati[ons] of a new kind," then how is this substantially different from God creating a new creation? Is it a re-creation of creation? God created everything, then the Fall, then God re-created everything, then the Millennium, and God re-re-creates everything again?

- BTW, don't some OECs who subscribe to the gap theory believe that there was a war in heaven, the fallen angels or demons (not sure if they make a distinction) were thrown down to earth, and fallen angels or demons were somehow responsible for all the predation, parasitism, pathogens, etc.? If so, then there seem to be striking parallels with the YEC argument for all the predation, parasitism, pathogens, etc.

- If God genetically changes a vegetarian lion into a carnivorous lion, a digestive tract that once digested grass like a cow to a digestive tract that now digests meat, or teeth or claws more like a rabbit or other herbivore to razor-sharp teeth and claws, then in what sense is it still the same lion? Say if God genetically changed me from an average human being into a human being that has wings so I can fly like a bird or gills so I can breathe underwater like a fish, then in what sense am I still a human being? Harvey Birdman or Aquaman, here I come!

Grab the mike!

Political stunts

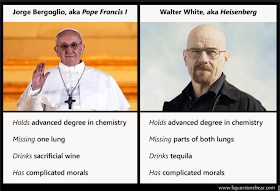

Pope vs Popes

|

| This is your pope on drugs ... |

First, here is what Pope Francis is saying. Westen says, “Pope Francis has recommended that the Church pull back from her perceived emphasis on ‘abortion, gay marriage and the use of contraceptive methods.’”

“We cannot insist only on issues related to abortion, gay marriage and the use of contraceptive methods,” Pope Francis said.

“This is not possible. I have not spoken much about these things, and I was reprimanded for that,” he added. “But when we speak about these issues, we have to talk about them in a context. The teaching of the church, for that matter, is clear and I am a son of the church, but it is not necessary to talk about these issues all the time.”

In the interview the Pope says that the Church’s preaching must begin first with the “proclamation of salvation.” “Then you have to do catechesis. Then you can draw even a moral consequence,” he said.

Other key lines from the Pope’s interview which pertain to this point include:

Scolding Pope Francis: “naïve and undisciplined” in recent interview

R.R. Reno, the editor of First Things, writes:

Francis, Our Jesuit Pope, First Things Blog, September 23, 2013:

I know Jesuits. They tend to be extremists of one sort or another. They’re trained to speak plainly, directly, and from the heart rather than according to the standard script.

Many passages in this interview reflect Pope Francis’ identity as a Jesuit. He speaks about himself in frank, personal ways that have the ring of authenticity. I don’t mean his comment that “I am a sinner,” which some secular commentators imagine a novel modesty. That sort of remark is Christianity 101. Instead, I mean: “I am a bit astute . . . but it is also true I am a bit naïve.” “I am a really, really undisciplined person.”

We’re not dealing with a modern politician who surrounds himself with handlers and carefully stays “on message.” Pope Francis is relatively unfiltered. He’s also not entirely self-consistent….

Tuesday, September 24, 2013

The recurrent laryngeal nerve

Fulano De Tal

RE The Recurring Laryngeal Nerve: The nerve's route would have been direct in the fish-like ancestors of modern tetrapods, traveling from the brain, past the heart, to the gills (as it does in modern fish). Over the course of evolution, as the neck extended and the heart became lower in the body, the laryngeal nerve was caught on the wrong side of the heart. Natural selection gradually lengthened the nerve by tiny increments to accommodate, resulting in the circuitous route now observed." - Richard Dawkins, The Greatest Show on Earth

Also observe that Dawkins simply propounds a just-so story to explain it. He doesn't provide any hard evidence.

God's vineyard

"What more was there for me to do for my vineyard than I have not done with it? When I expected it to yield grapes, why did it yield wild grapes?" Isaiah 5:4

Compatibilist: Well, you could have given us irresistible grace so we would have "most freely" [See Westminster Confession 10:1] yielded grapes pleasing to you.

Maul Panata Molinist: Put me in the circumstances I would have freely believed.

Jerry Walls Of course there may not be any such circumstances in any feasible world.

Maul Panata Of course it's possible God could not give them irresistible grace.

Also, I say that response confuses epistemic with metaphysical possibility.But, also see this:

http://www3.nd.edu/~jrasmus1/docs/philrel/counterfactual.pdf

Jerry Walls When the smoke clears and the dust settles, I would not be surprised if the two views left standing are Open Theism and Calvinism.

Maul Panata Jerry, I think you and I just found common ground there!

Apropos your comment, I find it interesting no one has asked why a God with infallible foreknowledge of future contingents expected the vineyard to yield grapes?

Jerry Walls Well, that could be anthropomorphic language, or expected in the sense of "would like to have seen it"

Maul Panata But once we start doing that, Calvinists can employ similar outs. But the force of the "gotcha" seemed to rest on taking phrases woodenly literal.

Jerry Walls Well, there does seem to be more involved in God doing all he can to elicit good grapes. And there are NUMEROUS passages in the prophets and elsewhere, where God emphasizes how he sent prophets, warnings, and so on over and over, which seems to imply he really wanted Israel to respond positively. So I don't think taking "expect" in the sense I suggest opens the door in the way you suggest. "Preferred" or "would have liked" is a reasonable reading of "expected," at least in English. Not sure if the Hebrew would suggest a different meaning. Lawson Stone, any thoughts here?

Maul Panata Well, for the Calvinist you are suggesting "what more was there for me to do?" is the problematic part, not the expect part. At least that's what is indicated by the "Calvinist" response to God's question. Right? You're saying "God is sincerely asking that. It's a woodenly literal question. He's requesting information. The Calvinist has an answer: 'You could have given them irresistible grace." This is the sense on which your gotcha rests, right?

Jerry Walls Yes, and on that matter, my point stands, irrespective of how "expect" is understood. Straightforward meaning is not the same as "woodenly literal." I think the essential point here is that God did indeed enable, encourage, and prefer a different response, and that this makes FAR more sense given libertarian freedom than compatibilist. And the same with many other passages in the prophets where God expresses disappointment, frustration, and the like. Even if there is some degree of anthropomorphism in the disappointment (and maybe there is not), the essential point stands.

Maladroit, malevolent theistic evolution

"When a beneficial mutation occurs, it tends to be distributed among the population. When a harmful mutation occurs, it tends to be rooted out. Hence, the effects of a single beneficial mutation tends to be greater than the effects of a single harmful one."

i) Don't harmful mutations greatly outnumber beneficial mutations?

ii) What if, say, a harmful mutation compromises the immune system, so that a population loses resistance to a deadly disease? Take hereditary degenerative diseases.

"Of course, we have evidence to go on, so we can ascertain whether evolution actually occurred."

What lines of evidence are you alluding to?

"I am inclined to believe that biological evolution (which excludes stellar evolution, abiogenesis, &c.) is improbable, but possibly not implausible."

That's equivocal. Are you saying biological evolution in general is improbable, or theistic biological evolution in particular?

"Because there is evidence to support it."

Once again, that's equivocal. Evidence for what? Evolution in general, or theistic evolution in particular?

"We simply lack the information to comment on how God guided the process of evolution. Nonetheless, we can say that God oversaw the process, so that there is teleology in nature, and man has a purpose."

What's your evidence that God guided the evolutionary process? What's your evidence that evolution is goal-oriented? What if God took a hands-off approach. What if God is shortsighted (a la open theism)?

"Then again, there are instances where evolution 'seems' more guided, e.g. the near-extinction of humans only 70,000 years ago."

i) Are you saying the survival of species is evidence of divine guidance? If so, does mass extinction indicate lack of divine guidance?

ii) You seem to be using Cro-Magnon as your frame of reference. I doubt Homo erectus or Neanderthal would share your sanguine view of natural teleology.

"However, I confess that I do not know God's purpose behind every event of evolutionary history. This is no more a weakness than not knowing God's purpose behind human history, e.g. the Holocaust. That, too, appears unguided and meaningless, but the knowledge that everything happens according to God's purpose assures us that it is not in fact unguided."

You seem to be taking evolution on faith, as if that's revealed truth.

"I wonder: Why do you think evolution is such an accepted scientific theory, having been exposed to so much confirmation…"

What confirmation do you have in mind?

"…and peer-review?"

That's a circular appeal.

"Is it all a conspiracy?"

Some Darwinians are quite upfront about their antipathy to Christian theism. In addition, scientists can suffer from tunnel vision.

"When a beneficial mutation occurs, it tends to be distributed among the population. When a harmful mutation occurs, it tends to be rooted out. Hence, the effects of a single beneficial mutation tends to be greater than the effects of a single harmful one."

My original statement wasn't limited to mutations. When I said, "For every lucky break, how many times does natural selection deal itself a losing hand? How can evolution stay in the game?"–that applies to natural history in general. All the haphazard threats to the survival of species.

"I wonder: Why do you think evolution is such an accepted scientific theory, having been exposed to so much confirmation and peer-review? Is it all a conspiracy?"

The life sciences are fiendishly complex. It's easy to lose your way in the labyrinth. Evolution supplies a unifying principle. Evolution puts the life sciences into a story. Gives it a plot. Drama. Characters. Linearity.

Never underestimate the power of storytelling. The perennial appeal of a good yarn. Consider the insatiable appetite for new movies.

The evolutionary narrative is more attractive at a distance. Heartless up close.

Theistic evolution softens some of the rough edges. Tries to convert the Darwinian dystopia into a utopia. Alls well that ends well.

"I'd haphazard a guess that beneficial mutations are sufficiently plentiful so as to ensure that evolution is possible."

Sounds like a faith-claim rather than a fact.

"Mutations also power micro-evolution, so if beneficial mutations are scarce, then we shouldn't be observing that either."

i) Aren't there ongoing debates about what mechanisms drive evolution?

ii) Also, opponents of evolution think organisms have some degree of built-in adaptability to new environments.

"If the entire population were affected by such a destructive mutation, then I guess they would be destined to hell in a handbasket. But I don't think that's very likely to happen in every case, as the affected individual(s) would be less likely to reach reproductive opportunities, and so the mutation would be rooted out of the gene pool."

People with hereditary degenerative disorders often live long enough to reach reproductive opportunities, for some these diseases only manifest in adulthood.

Also, within an evolutionary narrative, hominids mate as soon as they reach sexual maturity (i.e. adolescence). Generations are short.

"Genetic evidence, paleontological evidence, biogeographical evidence, and the like. Evolution simply is the best explanation for all the biological data."

Well, I've often stated my own views on that subject–including recently.

"It explains why we have non-functional genes in the same location as the functional counterparts in other mammals, it explains the existence of endogenous retro-viruses."

We need to guard against the temptation of jumping on the bandwagon of fast-moving, highly technical field. Even within the past few years I've seen significant retractions about previous confident claims.

"Its hypotheses are frequently confirmed (pace the frequent creationist claim that evolution is untestable), as in the case of the discovery of Tiktaalik, an ancient intermediate fossil, whose location was predicted by evolution."

Evolution "predicts" intermediates. But creationism doesn't deny ecological intermediates. And Tiktaalik has been analyzed in the creationist/ID literature.

"I rule out a shortsighted God by e.g. ontological arguments about a greatest possible being."

i) Even assuming the ontological argument is broadly sound (Which version? Anselmian? Leibnizian? Gödelian? Plantingian?), that requires subsidiary arguments to prove what makes certain attributes great-making attributes.

ii) Moreover, the evidence of guided evolution must be counterbalanced against evidence to the contrary. You can't treat the alleged evidence for evolution as the standard of comparison, then automatically dismiss counterevidence. For the evidence itself doesn't furnish a standard of comparison. You could just as well take the counterevidence as your standard of comparison.

"No, it was intended to show that evolutionary history doesn't solely appear unguided, but that there are also cases where species got surprisingly lucky. However, I reject that we can deduce design and guidance from either lucky breaks or unfortunes in history. It depends on what is God's goal, and I think you'd agree that God didn't intend to create a utopia."

ii) Likewise, why assume evolution is guided in the face of such an apparently haphazard and slipshod process?

"Indeed, not everyone's fate is as happy as ours, but I wasn't meaning to establish teleology from solely one happening."

You're talking about entire hominid species or races becoming extinct–just to further the goal? Aside from the inefficiency, isn't that pretty ruthless? Is that just a business expense, like the high mortality rate of serfs conscripted to build St. Petersburg?

"If misfortunes in evolutionary history reveal a divine absence, then misfortunes in human history should likewise."

Evolution isn't revealed dogma. It doesn't merit the same appeal to divine inscrutability. If you say evolution is a guided process, but you automatically discount empirical evidence to the contrary, then your position is arbitrary and fideistic.

"If hostility to Christianity explains the prevail of evolutionism, then why are most scientists willing to accept that there currently is no theory of the origin of life?"

Not for lack of trying.

"Also, many evolutionists are Christian."

They've been given an interpretive framework. They see the evidence filtered through the grid.

"Why do you think evolution is such an accepted scientific theory, having been exposed to so much confirmation and peer-review?...Tunnel vision is corrected by the sheer number of scientist, all of whom have different views and are in different situations, thus furthering their sole unifying cause, namely scientific knowledge. Of course, it probably isn't perfect, but surely it sufficiently safeguards the objectivity of the scientific enterprise."

You have a backwards notion of peer review. In the nature of the case, peer review enforces ideological and institutional conformity. Those who buck the system are banished to Siberia. Look at how entrenched global warming became.

"I'd add that the occurence of evolution therefore is evidence of some sort of intentional agent behind it."

Do you assume that if an airplane crashes, that must be due to intentional agency rather than mechanical error? You seem to begin with outcomes, then simply assume intentional agency must lie behind the outcome.

"but I don't see how it would actually get off the ground as a serious scientific theory unless there were something to back it up."

That assumes evolution is a serious scientific theory, which begs the question. It's certainly taken seriously by many. But, then, so is ufology.

steve9/19/2013 6:59 PMKaffikjelen

"My evidence that God guided the evolutionary process is: 1. evolution is true, and 2. Christianity is true. If Christianity is true, man isn't an accident."

That's illogical. God could be deistic. Or God could make nature an adaptive, stochastic system that takes on a life of its own.

"I rule out a shortsighted God by e.g. ontological arguments about a greatest possible being."

Assuming evolution is true, why should we only infer God's character from a priori arguments rather than a posterior effects like natural history?

"No, it was intended to show that evolutionary history doesn't solely appear unguided, but that there are also cases where species got surprisingly lucky. However, I reject that we can deduce design and guidance from either lucky breaks or unfortunes in history. It depends on what is God's goal, and I think you'd agree that God didn't intend to create a utopia."

You have a schizophrenic position. You think we should both judge and not judge the natural record by appearances. On the one hand, you think we should judge the nature record by appearances insofar as it (allegedly) bears witness to universal common descent by macroevolution. On the other hand, you don't think we should judge the nature record by appearances insofar as it bears witness to dysteleology, lack of foresight, lack of planning. On the face of it, natural history (a la evolution) bears witness to a God who's improvising on the fly. If evolution is goal-oriented, then then God is a poor marksman. To all appearances, he must be using nature for target practice to improve his aim. He keeps missing the target. Learning by trial and error. And a slow learner at that.

"If misfortunes in evolutionary history reveal a divine absence, then misfortunes in human history should likewise. God didn't share with us his reasons for permitting the Holocaust, and similarly, I don't need him to tell me what his purposes behind every seemingly non-ideal occurrence of evolution were."

If God used the process of evolution to eventuate man, then why were his means so ill-adapted to his ends? Why so many blind alleys, dead-ends, washed-out bridges, and cul-de-sacs?